LTAR’s Unique Approach to Sustainability

By 2050, the world’s population is expected to grow to more than 9 billion people, posing a critical challenge to agriculture in the United States and globally to provide enough food, feed, fiber, and fuel to sustain a growing population. As cropland area declines, and our natural resources face added stresses from extreme weather and changing climate, farm and ranch systems must become more productive and more resilient to remain sustainable—meaning simultaneously achieving adequate yields, profitability, and continued enhancement of the natural resources base.

Near Tombstone, Arizona, ARS technicians prepare a flume for monitoring runoff from the Walnut Gulch Experimental Watershed. (Stephen Ausmus, D2113-1) |

What Is LTAR?

To help meet these challenges, the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) established the Long-Term Agroecosystem Research (LTAR) network in 2011. LTAR is an ambitious, state-of-the art partnership among ARS, universities, federal agencies, and other research organizations to help farmers intensify agricultural food production while minimizing adverse effects on natural resources—and even further, seeking to enhance natural resources.

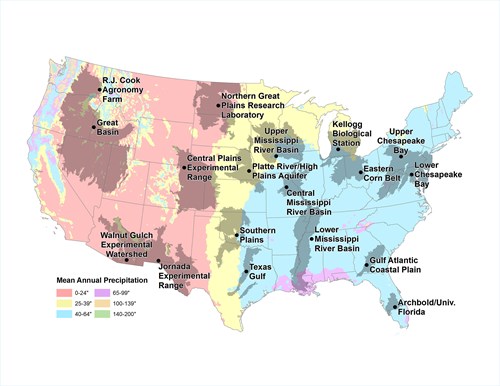

Each of LTAR’s 18 sites assesses the sustainability of existing and future production systems through research advancements. The LTAR network consists of rangeland and farm watersheds representing major U.S. agricultural production regions. Each site has its own production systems and landscape characteristics. (See details here and here).

- Archbold-University of Florida

- Central Plains Experimental Range

- Central Mississippi River Basin

- Eastern Corn Belt

- Jornada Experimental Range

- Great Basin

- Gulf Atlantic Coastal Plain Experimental Watershed

- Lower Chesapeake Bay

- Lower Mississippi River Basin

- Southern Plains Experimental Watersheds

- Michigan State University W.K. Kellogg Biological Station

- Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory

- Platte River-High Plains Aquifer

- R.J. Cook Agronomy Farm

- Texas Gulf Research Partnership

- Upper Chesapeake Bay Experimental Watersheds

- Upper Mississippi River Basin Experimental Watersheds

- Walnut Gulch Experimental Watershed

Most sites are located at ARS experimental locations with existing long-term research records. All sites share a commitment to collecting data on agricultural sustainability, climate patterns, ecosystem services, and natural resource conservation over the next 30 to 50 years. Some sites, however, have been collecting data for nearly 100 years. This rich legacy of research data can be analyzed to assess how well existing and experimental production systems are meeting the sustainability goals of yield, economic viability, and environmental enhancement.

Long-Term Agroecosystem Research Network map. Click here to go to interactive map. |

The LTAR landscapes serve as outdoor laboratories where scientists collect, store, analyze, and integrate accumulating data on agricultural production systems, the role of management in improving natural resources, and opportunities to improve economic returns. The data is stored in formats that enable scientists to address significant questions through shared research across science disciplines.

Each LTAR location addresses a “common experiment,” comparing “business-as-usual” production systems to “aspirational” production systems that incorporate the latest scientific and technological advancements.

What Makes LTAR Different?

“Traditional agricultural production research has focused primarily on the individual pieces of the production system, such as improving crop yield or input management efficiency,” says Charlie Walthall, ARS national program leader for Agricultural System Competitiveness and Sustainability. “The LTAR network, however, examines all aspects of production systems,” genetics (G), environment (E), and management (M)—and their interactions (GxExM).

“Despite the volumes of collected data about a field or past crop production, it’s key to know how a growing crop interacts with its environment and how management can interact with crop genetics and the environment to enhance production—while hopefully improving the health of the landscape,” Walthall explains. “Looking at these interactions—GxExM—allows farmers and ranchers to produce goods and services profitably with reduced risks to the environment.” This approach also helps close the gap between typical crop yields and possible crop yields, he adds.

LTAR research focuses on how interacting factors and processes affect production systems over time, and it provides insights that enable development of new production systems that will stand up to the test of time.

For example, during a recent severe drought, some Iowa corn growers who used new, specially bred, drought-tolerant varieties, but did not use management practices to protect the little soil moisture available, had a greater probability of crop failure, Walthall says. By combining appropriate management with new crop genetics, producers can increase their chances for more resilient—and profitable—production systems.

“Farmers tell us that they see their farms through the lens of the interaction of GxExM,” Walthall says. “By structuring our research to look at farm and ranch production the same way, we hope to accelerate production increases while improving our natural resources for future production. The LTAR enables us to ensure that new research advances will enable agriculture to meet the challenges of the future—and do so sustainably.”—By Sandra Avant, Office of ARS Communications.

Key Facts

- ARS created the Long-Term Agroecosystem Research (LTAR) network in 2011.

- Some LTAR sites have collected nearly 100 years worth of data.

- LTAR studies examine the interaction of genetics, environment, and management.

- Researchers store the data in accessible formats that enable collaboration.

Full Story