National Center for Ag Utilization Research

The Northern Regional Research Center (NRRC) in Peoria, Illinois, first opened its doors for business in December 1940. At the time, the center’s researchers focused their attention on developing new industrial procedures and value-added products or uses from surpluses of corn and wheat—the Midwest’s main crops. But other crops, notably soybean, became a priority in later years, followed most recently by novel oilseed crops including cuphea, field pennycress, and lesquerella.

From the start, the NRRC became synonymous with scientific innovation and excellence—especially in the area of fats, oils, carbohydrates, and fermentation research—with benefits not only to producers and consumers regionally, but nationally and internationally as well. See the table for a sampling of notable achievements from 1940 to 2000.

In 1990, by order of Congress, the NRRC was renamed the National Center for Agricultural Utilization (NCAUR) to better reflect the diversity of its research, which today is conducted at seven research units: Bacterial Foodborne Pathogens and Mycology, Bioenergy, Bio-Oils, Crop Bioprotection, Functional Foods, Plant Polymers, and Renewable Product Technology.

The scientists who work at these research units have been no less busy and creative in their endeavors than the center’s early teams. Indeed, an expanding list of crops, consumer expectations, and market opportunities have demanded as much. Below are a few examples of their success in keeping pace with such demands from 2000 to the present.

Sucromalt Sweetener

A slow-digesting carbohydrate sweetener, Sucromalt originated from the research of NCAUR chemists. Central to their approach was the use of food-grade enzymes from a cultured bacteria strain to convert corn, cane, or beet sugars into a novel, slow-release sweetener. Cargill, Inc., a cooperative research partner, licensed the sweetener technology and subsequently developed a low-glycemic-index syrup called “Xtend Sucromalt,” which can be added to a variety of foods and beverages, including Glucerna and Ensure nutrition shakes. When consumed, it is digested slowly but completely in the body, helping to stabilize blood sugar levels—a feature that makes the sweetener unique among similar products.

Biobased Lubricants and Additives

The expertise of NCAUR scientists has led to numerous biobased industrial products—often through cooperative agreements with private industry. For example, in 2002, the scientists teamed with a Defiance, Ohio, company, Agri-Lube, Inc., to produce a 1,000-gallon sample of a novel soy-oil-based hydraulic elevator fluid. National Park Service personnel evaluated the fluid in the elevator of the Statue of Liberty on Ellis Island, New York, and found it to be a high-performing alternative to petroleum-based formulations.

More recently, center scientists have teamed with an industry partner (Biosynthetic Technologies, Irvine, California) to realize the commercial potential of estolides for biobased lubricants. Estolides are fatty acids derived from high oleic-acid oilseed crops such as sunflower, canola, and lesquerella. They improve the cold-weather performance, oxidative stability, and other desirable properties of crankcase and other engine lubricants, whose global consumption is projected to exceed a market value of $65 billion by 2018 (Transparency Market Research).

Fuel Ethanol Advances

An early pioneer in this area, NCAUR continues to make significant advances in the conversion of starch- and cellulose-based sugars into ethanol as a cleaner-burning and “home-grown” alternative to petroleum-based fuels. The innovations are numerous and wide ranging, from demonstrating the importance of fermenting renewable sugars like arabinose and xylose from plant biomass like corn bran or energy crops like switchgrass, to utilizing powerful new enzymes such as beta xylosidase and specialized yeast strains and other microorganisms that can improve the efficiency of sugar-to-ethanol conversions.

In one case, the development of genetically engineered Escherichia coli bacteria resulted in ethanol yields of more than 90 percent from sugar hydrolyzates extracted from plant biomass, some of which cannot be fermented by distillers yeast. “The novel molecular engineering strategy used to construct these microbes is covered by a USDA patent, and the technology has been used for small-scale pilot plant fermentations,” says Bruce Dien, a chemical engineer with the center.

NCAUR biofuels research also extends to developing new, value-added uses for the coproducts of ethanol production. Approximately 14.3 billion gallons of the fuel were produced in 2014 (Renewable Fuels Association, Ethanol Industry Statistics), with dried distiller’s grains, corn gluten feed, and corn gluten meal being the chief coproducts. Corn gluten meal, for example, may prove a useful source of zein. This corn protein is primarily used as a water-repelling food and pharmaceutical coating, but may once again recapture myriad other uses previously lost to petroleum, such as adhesives, varnishes, binders, and films.

Together with its partners, NCAUR is also investigating new procedures for separating out components of the corn kernel itself—including the germ, hull, and endosperm fiber—to obtain residue oil, protein, gum, and useful compounds like ferulic acid, used as an antioxidant in skincare products and as a synthetic vanilla flavoring agent.

Advances in Biocontrols

The center has made significant advances in other areas as well, including the detection, genetic characterization, and prevention of mycotoxin-producing molds whose contamination of corn and other grain crops can pose a human-health hazard. On other fronts, NCAUR scientists have developed beneficial yeasts and bacteria to biologically control crop-damaging insects and pathogens, including the potato dry rot fungus Fusarium sambucinum, which inflicts U.S. postharvest tuber losses of $100 million to $250 million annually.

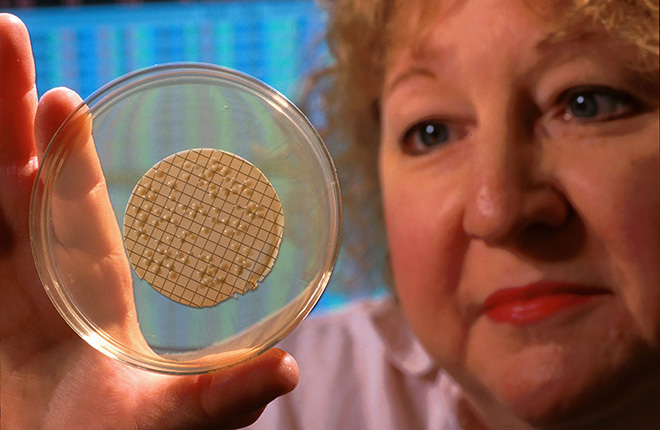

Vast Culture Collection

A survey of NCAUR’s achievements would be remiss in failing to mention the ARS Culture Collection, a repository begun in 1940 and which today houses nearly 100,000 microbial strains. These include historically significant microbes, such as the blue-green Penicillium chrysogenum that saved countless soldiers during World War II, and newer collections, like the Leuconostoc bacteria strains used to make the Sucromalt product. In a very real sense, the microbes are the engines that drive much of the center’s research endeavors, lifting them off the lab bench and catalyzing them into commercial reality.

As the food, fiber, fuel, and feed needs of a growing world population continue to increase, so too will NCAUR continue its tradition of scientific excellence in meeting those needs together with innovations that will help safeguard our natural resources for generations to come.

Consumer well-being is part of that continuum, adds Paul Sebesta, the center’s director. “Over the next several years, our researchers will also be developing new products and technologies specifically geared towards making sure the food we eat is safe, secure, and healthy.”—By Jan Suszkiw, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

“National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, Illinois” was published in the October 2015 issue of AgResearch Magazine.

Key Facts

- National Center for Ag Utilization Research.

- Located in Peoria, Illinois.

- Studies corn and soybeans and their byproducts.

- Also has research projects on bioenergy, food processing, and food safety.

Full Story