Monitoring Swine Health

“Summertime, and the livin’ is easy,” asserts the George Gershwin tune. For many people, summer fun includes agricultural fairs and petting zoos. Unfortunately, there can be a downside. Sometimes the animals on exhibit are infected with influenza (flu) viruses—maybe without signs—and in rare instances, these infections can be passed on to people. When this happens, the disease is called “zoonotic.”

While influenza illnesses are not always serious, the genetic profiles of these viruses are constantly changing. This poses problems for researchers trying to develop vaccines and treatments for these illnesses.

In the United States, most swine influenza cases reported before 1998 were caused by one strain of flu virus. Today, new strains that contain genetic material from human influenza appear more frequently, says Agricultural Research Service (ARS) veterinary medical officer Amy Vincent. Occasionally, strains with genes from avian influenza viruses (“bird flu”) are detected in pigs as well.

A scientist places swine cells under a microscope to observe them for signs of influenza virus infection. (Scott Bauer, K11003-1) |

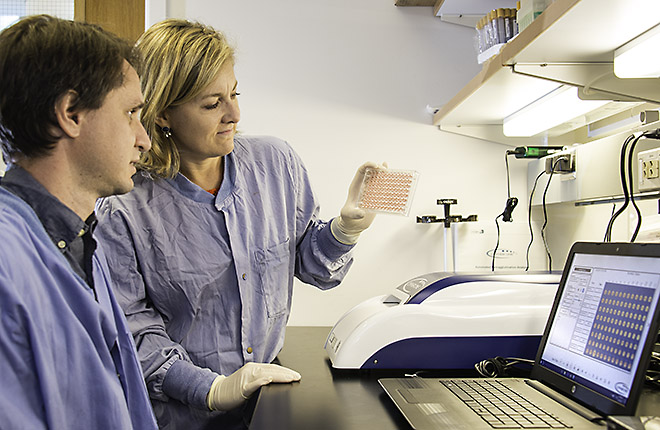

Because pigs are affected by many influenza strains, effective vaccination becomes more difficult. Vincent, microbiologist Eugenio Abente, and veterinary medical officer Kelly Lager in ARS’s Virus and Prion Research Unit in Ames, Iowa, work to help control swine influenza and protect pigs from it. Surveillance data contributes to the team’s research, which includes examining vaccines, the pig immune system, and emerging swine influenza strains.

In 2008 and 2009, ARS scientists joined forces with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to develop a national swine influenza surveillance program. Farmers and veterinarians voluntarily collect samples from sick pigs and send the samples for analysis to their local diagnostic laboratory or to APHIS’s National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) in Ames.

“The program initially grew from concerns about swine influenza viruses being detected in people and the emergence of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus,” says Vincent. “Influenza viruses in swine are different from human seasonal influenza viruses. Whenever a new nonseasonal influenza virus is picked up in people, CDC reports it to the World Health Organization.” When the CDC started looking for viruses with potential to spread and become an outbreak or pandemic, it began detecting an increasing number of swine viruses. In 2012, more than 300 cases were reported in which a particular subtype of swine influenza was isolated from people. There were more than 400 cases of all subtypes between 2011 and 2017.

“We proposed a national surveillance system in the U.S. pig population,” Vincent says. “Before 2009, the results of diagnostic work performed by state or private diagnostic labs were not in the public domain. This information was needed for animal health as well as public health.”

The surveillance system is administered through APHIS with the direct work mostly done through the National Animal Health Laboratory Network. If a virus isolate is recovered, it is sent to NVSL, which is co-located with the ARS National Animal Disease Center in Ames.

“We use surveillance data to do a series of analyses, tracking how viruses are evolving genetically in the field, and then examining isolates to see if infection properties have changed in the pig,” Vincent says. “We look at how related they are to what we’ve seen in the past and if new viruses are detected.”

Over the years, their work has shown that based on significant changes in emerging viruses, vaccines should be reevaluated for effectiveness when important changes are detected. “Our vaccine studies underscore the need for improving the process of updating vaccine strains in current vaccines and the need to consider other appropriate vaccine platforms that may improve immunity,” Vincent says.

Scientists also use surveillance data to document patterns of genetic changes in swine influenza viruses. This knowledge is important for monitoring possible emerging influenza threats. Data collected so far provides a baseline characterization of swine influenza virus genetic diversity in the United States from 2009 to today.

“We can now use the surveillance information to establish a benchmark to measure success of intervention strategies,” Vincent says. “These include timely vaccine and diagnostic updates for use in swine and humans as well as measures to prevent infection and transmission, such as changes in production practices or farm management.”—By Sharon Durham, ARS Office of Communications.

Key Facts

- Swine influenza viruses are constantly changing.

- Some swine influenza viruses can infect humans as well as pigs.

- ARS monitors these viruses in an interagency surveillance system.

- Genetic data helps researchers develop future vaccines.

Full Story