Fungal Hunter Prowls Soil for Plant Pathogen

Viewed through a microscope, the fungus Trichoderma asperellum resembles little more than delicate branched filaments. But make no mistake; it is a formidable hunter—of other microorganisms, that is.

Since 2006, Agricultural Research Service (ARS) plant pathologist Tim Widmer and colleagues have conducted laboratory and field tests to gauge T. asperellum's potential to biologically control Phytophthora ramorum. A plant pathogen, P. ramorum is the culprit behind sudden oak death, a disease of oak and other hardwood trees in coastal forests of California and Oregon.

|

|

Nursery growers are familiar with a different manifestation of P. ramorum, known as "ramorum blight." The disease afflicts rhododendron, viburnum, camellia, and other woody ornamental plants.

Chemical fumigation and soil sterilization are two common methods of keeping nursery stock blight free-and compliant with federal and state quarantine regulations meant to prevent the pathogen's spread.

Now, in collaboration with BioWorks, Inc., of Victor, New York, Widmer is evaluating ways to commercially formulate the T. asperellum fungus as a biobased alternative to such soil treatments, which can be costly (upwards of $3,900 an acre for some fungicides), dangerous to use, and harmful to beneficial soil organisms. The effort includes trials funded by the U.S. Farm Bill.

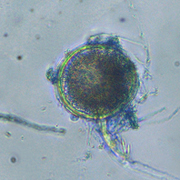

"This fungus, T. asperellum, is a mycoparasite, meaning it will actually attack and kill P. ramorum. It does this by penetrating different spore forms that the pathogen uses to survive and reproduce," says Widmer, who is with the ARS Foreign Disease-Weed Science Research Unit in Fort Detrick, Maryland.

In petri dish experiments at this ARS laboratory, and later in trials with potting mix at the National Ornamentals Research Site at Dominican University of California in San Rafael, the biocontrol fungus reduced P. ramorum levels by 60 to 100 percent, depending on which of the 12 strains of T. asperellum were tried. A chemical fungicide achieved similar results, but its effects proved temporary: 8 weeks later, the pathogen reemerged in the potting mix. Widmer suspects the fungicide temporarily halted the growth of the pathogen, but didn't kill it.

|

Left: Microscopic image of a Phytophthora ramorum spore. Right: Microscopic image of the Trichoderma asperellum fungus attacking a Phytophthora ramorum spore. (Photo by Tim Widmer D3826-1 | D3827-1) |

Under unfavorable soil conditions, P. ramorum can survive within thick-walled survival pods called "chlamydospores." But T. asperellum specializes in breaching such defenses. In its branched form, called "mycelia," the fungus coils around the chlamydospores and degrades their cell walls with powerful enzymes. The biocontrol fungus then enters the chlamydospores to feed, germinate, and start the cycle over again until little or no pathogen remains in the soil.

Indeed, in small-scale nursery trials conducted with the California Department of Food and Agriculture, drench treatments of the fungus reduced the pathogen to undetectable levels during the study's entire 3-month monitoring period.

Buoyed by those results, Widmer and his colleague Gary Samuels, a now-retired ARS mycologist, applied for and received a patent on the top-performing fungal strain, known as "04-22."

BioWorks has since licensed the strain and is collaborating with Widmer on developing and registering formulations that can be applied to nursery soils and potting mixes. Developed commercially, it could give growers another tool for battling ramorum blight, helping to safeguard vulnerable ornamental crops and forests alike. — By Jan Suszkiw, ARS Office of Communications.

Key Facts

- Phytophthora ramorum causes two plant diseases, sudden oak death and ramorum blight.

- Some chemical controls cost more than $3,900 an acre to use.

- ARS found a beneficial soil fungus can control the pathogen.

Full Story