The USDA Nematode Collection

The fifth in our series on the vital contributions of the ARS collections that conserve our genetic wealth. See Germplasm Collection Series under Additional Information.

More than a billion dollars worth of U.S. wheat has been sold to Brazil since 2000, thanks to the presence of a seed gall nematode in the USDA Nematode Collection.

Just a few years before then, Brazil had imposed a ban on U.S. wheat imports in fear of also importing wheat seed gall nematodes. But in 2000, Agricultural Research Service scientists proved to Brazilian authorities that a similar pest was already in Brazil. The proof was a slide of a seed gall nematode that had come from Brazil in 1953. This single slide of an obscure specimen in the USDA Nematode Collection, plus an examination of U.S. wheat by visiting Brazilians, got the ban cancelled, reopening a significant export market for U.S. wheat.

“Had this 47-year-old nematode not been in our collection, export to Brazil could have remained closed for years,” says ARS zoologist and Nematology Laboratory research leader David Chitwood. “That shows the value of maintaining a collection like this for the long term.”

|

|

Nematodes are Earth’s most numerous multicellular animals and include species that feed on bacteria, fungi, plants, insects, and animals. Some nematodes are beneficial, but others cause major damage. Root-knot nematodes alone cause 5 percent of all crop losses around the world each year. In total, nematodes cause $100 billion in global crop damage annually.

But identification of nematodes as friends or foes, knowledge that is important to many—from farmers to trade inspectors to public health officials—is based on a few physical structures that are very hard to differentiate, or even see, most of the time. And worse, these key structures can vary within a nematode species by life stage, sex, and just in general. “You can see why nematodes are so hard to identify,” Chitwood says. “In addition, there are thousands of nematode species that have never been named.”

This makes the USDA Nematode Collection, with its thousands of stored specimens, the most important reference guide in the world for identifying nematodes.

For example, in a recent 6-month period, USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service sent the collection 400 plant, soil, and nematode samples, 97 percent of them urgent, to identify nematodes intercepted at ports-of-entry or taken during domestic surveys.

To do so, it helps to have an expert on staff like collection curator Zafar Handoo.

Handoo, an ARS microbiologist at the Nematology Laboratory, made the official identification of the nematodes found in soil samples from Idaho potato-processing plants in 2006. Just six pale cyst nematodes (PCN) were found among thousands of bags of soil. But their identification resulted in suspension of U.S. fresh potato imports by Mexico, Canada, South Korea, and Japan, and kicked off a $70 million monitoring and control campaign to reopen the markets. Mexico, Canada, and South Korea eventually dropped their bans—except from PCN-regulated areas—and Japan allows very limited imports of U.S. fresh potatoes today.

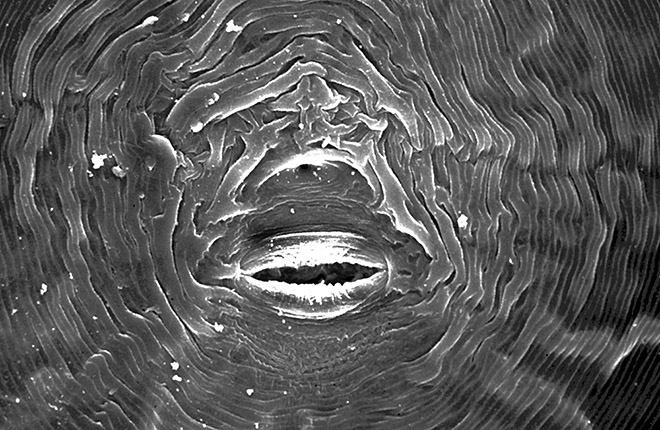

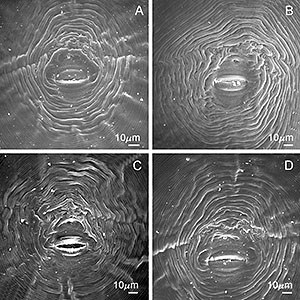

Close-up of a juvenile potato cyst nematode. (Image courtesy ARS Nematology Lab, D3600-2) |

In addition to serving as the identification reference, the collection also makes its slides available to researchers around the world. Many of the collection’s specimens are unique.

“Our oldest slide was collected in 1890 by Nathan A. Cobb, the father of nematology,” says Chitwood. “There are other remarkable slides of nematodes collected at USDA’s Arlington [Virginia] Farm. Some of these have never been found anywhere else, and that soil was paved over when the Pentagon’s parking lots were constructed.”

Among the more unusual subcollections is a group of marine nematodes from a German exploration of the South Pole in 1901. These may sound esoteric, but not that long ago they were requested by a Belgian researcher who used them to help revise the taxonomy of this group.

What does the future hold for the collection? The lab would like to build a library of DNA fingerprints to complement the morphological (structural) identifications.

“You have to be sure you have an identification correct before you make a DNA reference standard. Unfortunately, there are many nematode species for which we lack reference DNA,” Chitwood says.

The lab also plans to make detailed micrographs and drawings of nematodes and identifying parts accessible on the Internet.

“Global trade is growing, and that means problem nematodes could have greater opportunities to spread if everyone doesn’t stay alert,” Chitwood says. “People have tried to create computer programs to automate identifications. But they have never been able to develop any program that can deal with all of the complexities like a scientist with a good eye and a lot of experience can.”—By J. Kim Kaplan, ARS Office of Communications.

“The USDA Nematode Collection” was published in the May 2016 issue of AgResearch Magazine.

Key Facts

- The USDA Nematode Collection has thousands of stored specimens.

- Harmful nematodes cause $100 billion in global crop damage annually.

- USDA Nematode Collection specimens are important for accurate identification.

Full Story