A Culture of Innovation

The fourth in our series on the vital contributions of the ARS collections that conserve our genetic wealth. See Germplasm Collection Series under Additional Information.

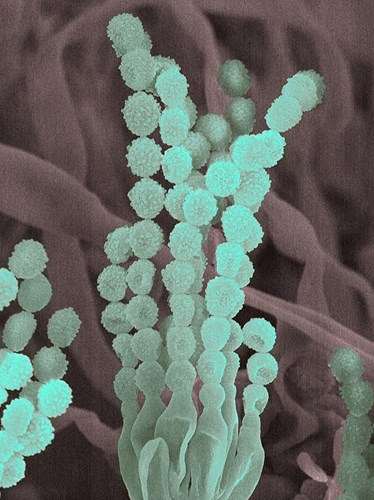

Charles Thom was hired by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 1904 to study the microbiology of Roquefort and Camembert cheeses. Two years later, he discovered Penicillium roqueforti and P. camemberti, the molds responsible for these tangy cheeses. Thom collected thousands of Penicillium strains in his career, and these became the beginnings of the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Culture Collection.

Now one of the world’s largest collections of freely accessible fungi and bacteria, the ARS Culture Collection was formally established in 1940 at the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research in Peoria, Illinois. One year later, in 1941, the collection’s vast array of Penicillium fungi proved critical to the hunt for a strain more effective at making penicillin than Alexander Fleming’s original mold. The discovery of such a strain helped scale up the antibiotic’s mass production in time to save many Allied soldiers wounded in World War II.

|

|

Today, the ARS Culture Collection, with its 100,000 strains of bacteria and fungi, is a significant biological resource for ARS scientists from which has come a long list of accomplishments. The following are just a few highlights:

-

Production of riboflavin (vitamin B2), dextran (blood extender), and xanthan gum, a thickener widely used in foods from ice cream to salad dressing

-

Genetic tests to detect new strains and toxin types of Fusarium head blight of wheat and barley, pathogens costing agriculture $1 billion annually

-

Sucromalt, a product that converts sugar into a low-glycemic sweetener used in a variety of foods and beverages, including Glucerna and Ensure

-

Identified Fusarium mold species as the cause of debilitating eye infections in contact lens wearers, a worldwide medical problem that emerged in the early 2000s

-

Tests to identify Listeria strains in foodborne disease outbreaks and assist food inspection and public health agencies.

“The collection’s 1,600 Listeria strains continue to provide service to the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” said geneticist Todd Ward, whose unit oversees the ARS Culture Collection.

“They send us samples from foodborne-disease incidents, and we genetically compare them against all the strains we have to confirm identification and to understand how the strain in one outbreak relates to other strains of Listeria. This tells them where outbreak strains are coming from and how Listeria is evolving during an outbreak and over time. Identifying the most dangerous strains and knowing what genetic changes are happening is critical to promoting food safety,” Ward says.

The collection also serves as a major national and international reference and resource for agriculture, industry, food safety, biotechnology, bioterrorism, and medicine. Last year alone, the ARS Culture Collection sent out more than 5,500 isolates, answering requests from across the United States and 43 other countries. Its isolates have been cited in more than 48,000 scientific publications and patents, reflecting the collection’s broad impact and importance.

A large National Institutes of Health-funded project at the University of Illinois recently turned to the collection’s extraordinary diversity and depth to screen 7,000 actinomycete isolates, looking for ones with genes to produce new molecules with certain useful properties.

“Fourteen strains out of those 7,000 were found to produce completely new types of antibiotic compounds with enough potential that eventually one or more of them could be the next great natural herbicide or alternative treatment for a drug-resistant pathogen,” says David Labeda, curator of the collection.

But he points out that even a collection as large as ARS’s still only represents a tiny fraction of the microbial diversity in nature. “Yet, I am continually surprised to see species just being described in the scientific literature that have been preserved in the collection for decades,” Labeda says.

One special effort towards preservation that the ARS Culture Collection has always made is to absorb rare collections orphaned because of staff retirements, research direction changes, or funding cuts. In 1987, the ARS Culture Collection took in the Howard Dulmage Collection of Bacillus strains that infect insects. This proved to be especially fortunate when the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) turned to the collection in 2001 for help with tracing the origins of the anthrax spores from the letter attacks on NBC’s Tom Brokaw, the New York Post, and others. There was a Bacillus contaminant among the spores, and it was hoped that if the Bacillus was unique, it could provide a lead in the anthrax investigation.

By devising a genetic test to rapidly screen their large number of Bacillus strains, the collection’s scientists were able to provide the FBI with the forensic information it needed.

As important as the collection’s past contributions have been, Labeda expects it will be even more important to the future of agricultural research and scientific discovery. “We will see new applications in an incredibly wide variety of areas. In some cases, we won’t know what we will need until we need it.”—By J. Kim Kaplan, ARS Office of Communications.

“A Culture of Innovation” was published in the April 2016 issue of AgResearch Magazine.

Key Facts

- The ARS Culture Collection contains about 100,000 bacteria and fungi strains.

- The Collection was established in 1940 and is publicly accessible.

- It has contributed to many scientific advancements.

Full Story