Downy Mildew Helps a Bad Hitchhiker in Lettuce

Downy mildew is usually a lettuce grower’s worst nightmare; it’s the biggest problem in lettuce production. Multiple applications of protectants are usually needed to control the fungus-like water mold Bremia lactucae that causes downy mildew, and it may cost millions of dollars more in bad years when it can wipe out entire crops regardless of treatment.

But ARS microbiologist Maria Brandl at the Produce Safety and Microbiology Research Unit in Albany, California, is more interested in another pathogen that sometimes can be traced to lettuce fields: Escherichia coli O157:H7. This highly virulent bacterium is one of the most common causes of foodborne illness in people. While food sources of E. coli O157:H7 are as diverse as undercooked beef, sprouts, raw dairy, shelled walnuts, fruits, and vegetables, multi-state outbreaks have been traced back to lettuce.

How this pathogenic bacterium gets ensconced on lettuce plants has been a persistent mystery. Various possible pathways have been investigated, from wandering feral pigs to contaminated irrigation water to the feces of snails, flies, and flying birds.

Lettuce leaves are not normally a welcoming environment for enteric (intestinal) bacteria like E. coli O157:H7; the leaf surface is actually a harsh location where many microbes struggle to survive. But the epidemiological evidence is undisputable.

So Brandl has been on the lookout for special circumstances that might allow E. coli O157:H7 to multiply. In earlier research, she found that E. coli O157:H7 preferred cut, injured, and younger leaves to undamaged and older ones. Then she collaborated with ARS geneticist and lettuce breeder Ivan Simko from the Crop Improvement and Protection Research Unit at Salinas, California.

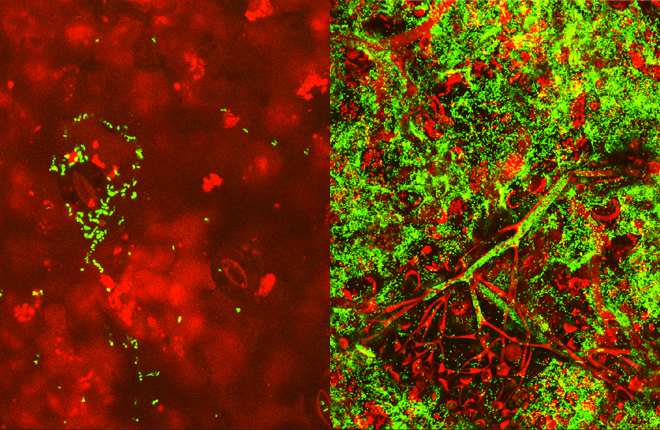

They considered that E. coli O157:H7 may team up with the downy mildew pathogen, which invades leaf cells when plants are wet, breaking down the leaf tissue and eventually creating chlorotic (yellowing) and necrotic, dead spots.

What they found was eye-opening, generating enough attention that their journal article in BMC Microbiology was accessed online more than 1,000 times in the 2 months after its publication.

“Given favorable growing conditions of warmth and free water on the leaves, E. coli O157:H7 numbers increased 1,000-fold more in downy mildew lesions than on healthy lettuce leaf tissue,” Brandl explains. “We also saw much greater survival of E. coli O157:H7 on leaves with downy mildew disease than on healthy tissue when the lettuce leaf surface was dry, a condition that typically leads to the rapid death of most E. coli O157:H7 cells.”

Similar relationships have not been reported with other pathogens. For example, lesions caused by lettuce mosaic virus did not promote the growth or survival of Salmonella, nor did infection of spinach by Pseudomonas syringae affect E. coli O157:H7 growth. So it does not appear that the physical occurrence of lesions alone is assisting E. coli.

To further test if downy mildew plays an overt role in E. coli O157:H7 colonization of lettuce or if it is a coincidence of conditions, they turned to lettuce RH08-0464, the breeding line that ARS geneticist and lettuce breeder Ryan Hayes in Salinas recently released in collaboration with Simko.

“We found that E. coli O157:H7 could not grow as well in the lesions of the more resistant lettuce line RH08-0464 line as it did on a conventional commercial variety called Triple Threat, which is highly susceptible to downy mildew,” Simko reports.

Knowing there is a connection is one thing; putting it to use is another.

One potential connection Brandl and Simko are following is that downy mildew resistance in lettuce line RH08-0464 may also effect greater expression of the antimicrobial protein PR-1. This protein contributes to a plant’s general defense against microbial colonization, and the researchers found it was expressed at a higher level in lettuce line RH08-0464 than in Triple Threat in their study.

But the exact factors that cause less growth of E. coli O157:H7in the more resistant line still need to be carefully explored. The next step will be to look for “a relationship between broad immunity and survival of E. coli O157:H7 in a larger number of lettuce lines and varieties before we will have any information about a genetic concept,” Brandl and Simko explain.

If any genetic hurdle to E. coli O157:H7 colonization could be bred into commercial lettuce varieties along with downy mildew resistance, it would add a new defensive line in lettuce safety, helping farmers to improve the microbial safety of their crop as well as control their number-one plant disease problem.—By Kim Kaplan, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

“Downy Mildew Helps a Bad Hitchhiker in Lettuce” was published in the July 2015 issue of AgResearch Magazine.

Key Facts

- The bacterium Escherichia coli O157:H7 causes foodborne illness.

- Outbreaks of this pathogen have occurred on lettuce in the past.

- In warm, wet conditions E. coli O157:H7 thrives in downy mildew lesions on lettuce.

- E. coli numbers in downy mildew lettuce lesions can be 1,000-fold higher than on healthy lettuce leaves.

Full Story