Dietary Products

Some are Underresearched, Overmarketed

While surfing the Web, you may have seen ads promising “one tip to a flat belly.” After clicking on the ad, you jump to a website where official-looking major-news-outlet logos appear. After reading more details about the advertised product, if you clicked “purchase,” you took a step closer to achieving the product promoter’s goals.

There are several products, such as African mango supplements, that appear at the end of these “one tip” ads. But the real tip is accurate consumer information about the products.

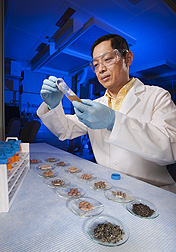

The popular African mango (AM) supplements are based on extracts from the seeds of Irvingia gabonensis. At the Beltsville [Maryland] Human Nutrition Research Center, Agricultural Research Service chemist Pei Chen and postdoctoral associate Jianghao Sun studied AM supplements and found that none of the labels on the ones they tested provided accurate information for consumers.

During the past decade, other researchers have conducted human clinical trials and published results indicating that AM seed extracts may have some effect on lowering body weight.

“All of the labels of African mango dietary supplement products sold in the United States list African mango seed extract as the major ingredient,” Chen says. Chen and Sun conducted studies to find out whether the supplements contain what they say they contain.

|

|

Noting a lack of past chemical analyses of AM seeds, seed extracts, and dietary supplements in the scientific literature, Chen and Sun used a method called “ultra high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry” to perform such an analysis.

For the study, the team procured AM seeds that had been imported directly from Africa. The samples came with a voucher verifying their authenticity and were further authenticated by a U.S. Pharmacopeia scientist. The team also procured three AM seed extracts and five different AM dietary supplements to analyze. The three seed extracts were imported from China, and the supplements were purchased online in the United States.

During testing, Chen and Sun identified a group of major components in the verified AM seeds: ellagic acid; mono-, di-, and tri-O-methyl-ellagic acids; and their related glycosides. “These components can be used as authentication markers when testing the contents of AM extracts and related AM dietary supplements for quality control,” says Chen.

Among the five AM dietary supplements tested, only one contained trace amounts of AM seed. The other four supplements and the three AM seed extract samples did not contain any detectable amount of authentic AM seed.

When Foods Are Hyped in the Media

“Super foods,” is a nonscientific term sometimes used by both media and advertisers to promote certain whole foods that are high in nutrients or phytochemicals. These compounds are often extracted and put into dietary supplements or added to other foods by the food and supplement industries. The aim is to appeal to the consumer’s hope for health benefits from consumption.

Significantly, there is scientific evidence that eating a wide variety of foods is important to the body’s ability to absorb nutrients, and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans promotes a diet that consists of “co-consumption” of a variety of recommended foods to achieve a balanced diet and sufficient nutrient intake.

ARS scientists in Boston, Massachusetts, have authored a book chapter focusing on one widely touted food—açaí (pronounced ah-sah-EE). Açaí is a reddish-purple berry, which grows on large palm trees that are in the Euterpe genus and are native to Central and South America. Açaí has received attention among food scientists, and now a variety of açaí products—juices, tablets, capsules, and dissolvable powders (freeze dried or spray dried)—are being marketed to consumers.

The book chapter was authored by molecular biologist Shibu Poulose and research psychologist Barbara Shukitt-Hale, who are with the Neuroscience and Aging Laboratory, which is part of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston. Studies in humans are needed to assess potential health benefits of any single food, and the authors report that there have been a limited number of studies exploring the health effects of açaí berry in humans.

Focusing on Facts

In 2013, ARS nutritionists Seema Bhagwat, David Haytowitz, and Joanne Holden (retired) prepared and launched the USDA-ARS Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods: Release 3.1. The amount of flavonoids in foods is of interest because of their purported beneficial health effects.

Though there are thousands of individual flavonoids, the new release contains composition values for 26 commonly occurring dietary flavonoid compounds in 506 food items. For example, for each 100 grams of açaí, the flavonoid database lists the amount of cyanidin in fresh berries at 53.64 milligrams (mg), frozen berries at 61.94 mg, and powdered açaí fruit/pulp/skin at 200.96 mg.

“The freeze-dried açaí powders that are commonly used for nutrient-composition testing and analysis have had almost all of the fruit’s moisture removed,” says Haytowitz.

In their book chapter, Poulose and Shukitt-Hale report that published scientific tests and analyses have shown that açaí fruit and pulp contain other phytochemicals, including different flavonoids, phenolic acids, and stilbenes; and nutrients, including vitamin A, beta-carotene, copper, iron, retinol, calcium, protein, and fiber. Açaí also is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as omega-3 and omega-6, and monounsaturated fatty acids. For example, its oleic acid content reportedly rivals that of olive oil, according to the authors.

Gauging how well the body breaks down phytonutrients in foodsand whether such compounds are available for absorption in the body requires separate testing and analysis. At this time, there is a dearth of scientific evidence proving health effects in humans from consuming açaí. And there is a need to test foods associated with health claims by nonscientific sources.

The book chapter appears in “Tropical and Subtropical Fruits: Flavors, Color, and Health Benefits,” published in 2013 by the American Chemical Society.—By Rosalie Marion Bliss, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Human Nutrition, an ARS national program (#107) described at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

To reach scientists mentioned in this article, contact Rosalie Marion Bliss, USDA-ARS Information Staff, 5601 Sunnyside Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705-5129; (301) 504-4318.

"Dietary Products: Some are Underresearched, Overmarketed" was published in the March 2014 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.