Treasures of the National Agricultural Library

Timeless Works of Fungi

Mushroom hunters—and their more scientific colleagues, the mycologists—are accustomed to seeking their prizes in unusual places. But finding mushroom treasures inside the National Agricultural Library (NAL) is a unique encounter even for them.

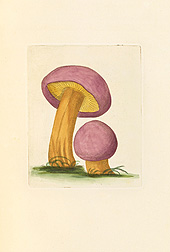

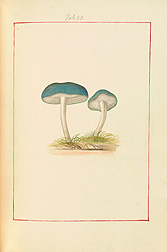

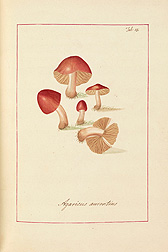

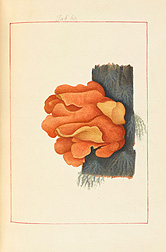

For preserved in NAL’s Special Collections is a truly irreplaceable specimen: Icones Fungorum circa Halifax Sponte Nascentium, James Bolton’s original, hand-drawn manuscript of his highly regarded published work, An History of Fungusses, Growing about Halifax.

The manuscript is 6 volumes with 242 exquisite watercolors of fungi, mostly life-size, with extravagant detail about where Bolton collected the specimen and what he discovered of its biology.

|

|

A self-taught naturalist and artist, Bolton came from a family of weavers in Yorkshire, England. His original patron, Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, Dowager Duchess of Portland, had the largest natural history collection in Great Britain. After her death in 1785, Henry Noel, Earl of Gainsborough, to whom the manuscript is dedicated, supported Bolton’s work.

Bolton is credited with describing hundreds of fungi, many new species or new British records, although the number was later reduced by taxonomic reclassifications.

When published, in 1788, An History of Fungusses established Bolton’s place in mycological history. Because of the exactness of his depictions, it became a standard resource for mushroom identification. It is as regularly quoted today as it was by Elias Magnus Fries, the founding father of mushroom taxonomy, in the 1800s, according to Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh head of mycology (retired) Roy Watling. The late 1700s and early 1800s were dynamic times for mycology, with experts contending in identifying new species and expanding and resolving taxonomic order.

Bolton “was criticized as being both a ‘lumper’ and a ‘splitter,’ but we now think of him as being mainly the latter. He designated Bolbitius titubans and B. vitellinus as two separate species and recognized all five different species of Armillaria (honey fungus), when these had been put together by the rest of the early mycologists. The ultimate tribute to his outstanding talents is that his ideas have been confirmed by modern mycology,” Watling says.

|

|

The published version of Bolton’s manuscript fills just 4 volumes, each nearly the same dimensions as the manuscript, with 182 plates, 40 of them grouped with more than 1 illustration to a plate. But what NAL Special Collections has that is unique is Bolton’s original manuscript.

According to a 1932 Transactions of the British Mycological Society article written by famed U.S. Department of Agriculture plant pathologist and mycologist Cornelius Lott Shear, NAL purchased the manuscript for 1,000 Swiss francs from “an old bookseller in Zurich, Switzerland.”

The published edition contains all of the illustrations that are in the manuscript, plus a few additional. In the manuscript, the watercolors are arranged in the order in which the fungi were collected and drawn. But when the watercolors were transferred to copper plates for printing, they were rearranged and renumbered, according to Shear. Bolton wrote, in the manuscript notes, that he made some of the drawings directly on the copper plates from fresh specimens for the published illustrations.

|

|

Since Shear wrote of it in the third person, he probably was not the manuscript’s purchaser. But NAL has not yet located the records of how it obtained the manuscript or what brought it to the library’s attention in 1932.

Some think it could have been John Stevenson who discovered the Bolton manuscript or advocated for its purchase. Stevenson was in charge of the USDA National Fungus Collections from 1927 to 1960 at the Agricultural Research Service’s Beltsville [Maryland] Agricultural Research Center.

Amy Rossman, who recently retired as research leader of the ARS Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory in Beltsville, which now administers the fungus collections, concurs with the Stevenson possibility.

|

|

“Stevenson was a renowned collector who amassed a wonderful library about all things mycology,” Rossman says. “He apparently even spent a lot of his own money for what he considered important.”

Just before Rossman retired, a large cache of historical papers from her lab, including many from Shear and Stevenson, was turned over to NAL for proper storage and to provide access to researchers, says Susan Fugate, head of NAL Special Collections.

“As we organize the materials, we will be keeping a special eye out for any that mention the Bolton manuscript and how NAL came to acquire it,” Fugate says.

Only in the Manuscript

The manuscript has significance far beyond its prized historical value. One unquestionable extra is that its pages preserve three actual specimens of fungi. Except for a specimen preserved at Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, and a few recently discovered in a brown paper packet at the Sunderland Museum, these are the only fungi collected by Bolton known to have survived.

The description opposite each drawing in the Bolton manuscript “often makes fascinating reading, and frequently provides more detailed information than the rather brief comments found in the printed book,” wrote John Edmondson in a memoir that accompanied an exhibition he organized on Bolton’s work at the Liverpool Museum in 1995. NAL loaned the manuscript to the museum for the show, possibly the first time it had been publicly displayed since 1932.

Edmondson also raised the question of whether this is truly the “original” manuscript, as Shear claims. Edmondson holds that its watercolors are copies prepared from earlier drawings, and the published plates were based on those earlier drawings.

According to Shear, the last mention of the originals before 1932 was in The Halifax Naturalist in 1902 that said, “it is doubtful whether the originals for the History of Fungusses are still in existence. They were probably destroyed by fire when the old hall at Exeton [the Earl of Gainsborough’s family seat] was burned in 1810.”

Shear said an appeal to the Zurich bookseller for information about the manuscript’s missing background brought only that it had been bought at a sale. But those who possessed it during the 141 years between the final volume’s publication and its 1932 purchase must have cared for the manuscript well, as it is in excellent condition.—By J. Kim Kaplan, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

Susan H. Fugate is head of Special Collections, USDA-ARS National Agricultural Library, 10301 Baltimore Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705; (301) 504-5876.

"Treasures of the National Agricultural Library: Timeless Works of Fungi" was published in the August 2014 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.