Human Medical Advances May Result From Tree Nut Research

Prescription drugs that today help patients fight severe fungal infections might tomorrow be even more effective. Laboratory studies by former Agricultural Research Service research leader Bruce C. Campbell, ARS molecular biologist Jong H. Kim, and their colleagues suggest that pairing conventional antifungal medications with natural, edible plant compounds such as thymol—extracted from the popular herb thyme—can work synergistically with some of these drugs to boost their healing effects.

The studies are an unexpected “spillover” from the scientists’ ag-based, food-safety-focused research, which they conduct at the ARS Western Regional Research Center in Albany, California.

Each year, millions of Americans are diagnosed with diseases caused by pathogenic fungi. The most serious of these, invasive fungal infections, are more than skin deep and can be deadly. What’s more, some of the fungi that cause these infections are developing resistance to well-established antifungal drugs.

For their work, Campbell and Kim have targeted several key groups of fungi: Aspergillus molds, which can severely damage the lungs or other organs; Candida yeasts, which sometimes cause life-threatening conditions if they enter the bloodstream; and a Cryptococcus yeast that can lead to fungal meningitis, a dangerous swelling of tissue around the brain and spinal cord.

“With the appropriate medication, administered early, most healthy people can fend off infections caused by these fungi,” says Campbell. “But current treatments may take many months, can be expensive, may lead to serious negative side effects, and can contribute to the increasing presence of resistant strains.”

People with a compromised immune system, such as cancer patients undergoing bone marrow or organ transplants, and individuals with AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), are among the most susceptible to invasive fungal infections.

In their ongoing research, Campbell and Kim have shown that drug and natural agent duos are significantly more effective in debilitating target fungi than if either the drug or agent had been used alone.

Using plant-derived compounds to treat fungal infections is not a new idea, nor is that of pairing them with antifungal medications. The Albany team’s studies have, however, explored some apparently unique pairs and provided some of the newest, most detailed information on the mechanisms likely responsible for the impact of powerful drug-natural agent combinations.

Food Safety Studies Targeting Aspergillus Attract Medical Researchers’ Interest

It was Campbell and Kim’s research on Aspergillus species that initially attracted the attention of medical and public health researchers in the United States and abroad. This mold is found worldwide in air and soil. Growers of pistachios, almonds, corn, cotton, and some other crops know that it can infect their harvests and produce aflatoxin, a natural carcinogen.

“Aflatoxin-infected crops must be identified and removed from the processing stream,” says Campbell. “At times, this can result in huge economic losses.” That’s why there’s an ongoing demand for research that will yield new, robust, affordable ways to control the fungus.

To meet that need, Campbell, Kim, and coinvestigators have—since 2004—carefully built a portfolio of potent, plant-based compounds that either kill A. flavus or thwart its ability to produce aflatoxin. Further research and testing might enable tomorrow’s growers to team the best of these natural agents with agricultural fungicides that today are economically infeasible to use.

The A. flavus of orchards and fields is also among the Aspergillus species that can cause lung damage in immunocompromised people. If exposed to the fungus in a moldy home, for instance, they may inhale more of its spores than their bodies can handle. Though an A. flavus relative, A. fumigatus, is the main pathogen associated with this invasive infection, A. flavus and a third causative species, A. terreus, are also of concern.

Thymol Performs Well in Many Tests

In a study published in 2010 in Fungal Biology, the team zeroed in on these three Aspergillus species. The study showed that thymol, when used with two systemic antifungal drugs—fluconazole or ketoconazole—“inhibited growth of these fungi at much lower than normal doses of the drugs,” says Kim.

The study also showed that some combinations don’t work. For example, thymol improved the effectiveness of the drug amphotericin B against A. flavus and A. fumigatus, but it undermined the drug’s effectiveness against two of three strains of A. terreus tested, according to Kim.

In an investigation reported last year in Applied Microbiology, thymol was one of a half-dozen promising natural compounds that were teamed with drugs and tested against Candida and Cryptococcus species.

Other natural compounds selected for this battery of tests included cinnamic acid from cinnamon tree bark; salicylic acid, like that found in willow; and 2,5-DBA (dihydroxybenzaldehyde), found in chard.

Each natural agent was paired with each of three different antifungal medications—amphotericin B, fluconazole, and itraconazole.

Importantly, none of the natural compounds interfered with the effectiveness of any of the drugs. Also notable: 2,5-DBA “worked synergistically with almost all of the drugs used against the Candida and Cryptococcus species,” Kim says.

Thymol added to the impact of all three drugs in the Candida tests and one of the three in the Cryptococcus experiments.

What Fungal Genes Do Natural Compounds Target?

Additional studies by this team are providing new evidence to support earlier findings at Albany and elsewhere, which suggest that the natural agents sabotage the target fungi’s ability to recover from oxygen-related problems referred to as “oxidative stress.”

“Antifungal drugs can trigger oxidative stress,” Kim explains. “Fungi may respond by quickly activating a complex defense system, which can include producing protective enzymes that act as antioxidants.”

In this research, the team used both natural and laboratory-built versions, called “analogs,” of certain compounds, including modified forms of thymol, cinnamic acid, and vanillin, like that from vanilla bean.

The studies suggest that these modified agents interfere with fungal genes. Normally, those genes enable the fungi to produce the necessary antioxidant enzymes. Some examples are sod1 and sod2, which cue production of superoxide dismutases, and glr1, which contains the blueprint for another powerful antioxidant enzyme, glutathione reductase. An article published in 2011 in Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials tells more.

It’s Called “Chemosensitization”

The scientists refer to the synergistic interaction of med and natural agent as “chemosensitization”—a term borrowed from chemotherapy treatments for cancer patients. “The natural agent ‘sensitizes’ the target fungi, making it more vulnerable to the effects of the drug,” Campbell explains.

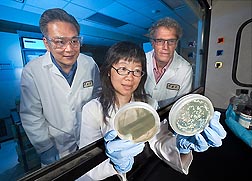

“Our petri-dish tests,” says Campbell, “are a starting point. Many years of medical research are needed to provide the data necessary for federal approvals of new medical uses of natural agents. But the fact that the chemosensitizing agents are natural may help simplify the approval process.”—By Marcia Wood, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research supports the USDA priority of ensuring food safety and is part of Food Safety, an ARS national program (#108) described at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

Bruce C. Campbell and Jong H. Kim are in the Plant Mycotoxin Research Unit, USDA-ARS Western Regional Research Center, 800 Buchanan St., Albany, CA 94710; (510) 559-5846 [Campbell], (510) 559-5841 [Kim].

"Human Medical Advances May Result From Tree Nut Research" was published in the October 2012 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.