New Test Detects Bone Disease in Red Angus

|

|

When a rare and deadly birth defect called “marble bone disease” struck Black Angus cattle in the 1960s, producers had little alternative but to cull all animals related to affected calves in an effort to get rid of the mutation. When the same disorder resurfaced in Red Angus 3 years ago, scientists had a better and less costly option: Develop a DNA test to identify carriers responsible for the disease.

The return of marble bone disease, also known as “osteopetrosis,” became a high priority for Larry Keenan, director of breed improvement at the Red Angus Association of America (RAAA) in Denton, Texas. To stop it from spreading, Keenan teamed up with Tim Smith, a chemist in the Genetics and Breeding Research Unit at the Agricultural Research Service’s Roman L. Hruska U.S. Meat Animal Research Center (USMARC) at Clay Center, Nebraska, and Jonathan Beever, a molecular geneticist at the University of Illinois in Champaign.

A bone disorder that affects humans, cattle, and other animals, osteopetrosis is characterized by overly dense yet brittle bones that shatter easily. Calves that suffer from the mutation have deformed skulls, receding lower jaws, and protruding tongues. They usually are stillborn or die within 24 hours of birth.

Though osteopetrosis is not common in cattle, it has been reported in Hereford, Simmental, Holstein, and Angus breeds in the past, Smith says.

“Calves have to inherit the mutation from both parents,” he says. With the recent incident in the Northern Plains, there was significant concern because the breed’s most popular bull was related to some of the animals that had produced osteopetrosis-affected calves.

“A lot of calves were indirectly linked to that bull, so breeders wanted to make sure that they weren’t continuously putting the DNA for the disease into their herd,” adds geneticist Tara McDaneld at USMARC.

Smith, McDaneld, Beever, and geneticist Tad Sonstegard at the Henry A. Wallace Beltsville [Maryland] Agricultural Research Center collaborated with veterinary researchers at the University of Nebraska and University of Wyoming to identify the gene mutation responsible for the disorder and to develop a diagnostic test that identifies osteopetrosis carriers.

Tissue samples of seven affected calves were first examined for bovine viral diarrhea virus, a known infectious cause of osteopetrosis, but the results were negative. However, pedigree analysis of the seven calves revealed both maternal and paternal common ancestry, suggesting an association between their genes and the disease.

Scientists compared DNA from affected Red Angus calves and their carrier parents to DNA from unaffected animals. They then searched the entire genomes of all calves for chromosomal segments common to the affected animals, but different from the normal animals.

|

|

A Tool for the Task

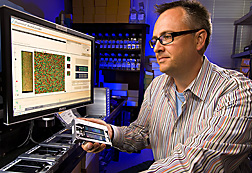

The Illumina Bovine SNP50 BeadChip, developed earlier by ARS researchers, along with industry and university partners, was used to identify suspect genes. The BeadChip, a glass slide containing thousands of DNA markers, identifies relationships between markers simultaneously.

“We had just the right tool to genotype DNA samples from animals with this mutation,” Sonstegard says. “Once samples were assembled and extracted, running the chip didn’t take very long.”

A single chip generates more than 50,000 genotypes for each animal. DNA samples were applied to the BeadChip, chemically labeled, and scanned to produce genotypes.

“We were looking for those regions from the affected calves where the chromosome was similar on both the mother’s copy and the father’s copy,” Sonstegard says. “We were able to detect through an analysis program when it was homozygous—having two copies of the same gene—only in a specific region of chromosome 4.”

Identifying a Mutation

A segment on cattle chromosome 4 contains SLC4A2, a gene necessary for proper osteoclast maintenance and function, McDaneld says. Osteoclasts are types of cells responsible for breaking down old bone during bone development and remodeling.

In the osteopetrosis-affected calves, researchers found that some of the SLC4A2 genetic material had been deleted. The discovery of the deletion in this gene was a first for cattle, McDaneld says.

While the cattle study was being conducted, scientists elsewhere were studying bone development in mice. They intentionally created a similar mutation in SLC4A2 to determine the function of the gene, and it was observed to cause the same marble bone disease phenotype, McDaneld says. The fact that the exact same gene in mice was responsible for the osteopetrosis mutation confirmed the findings in Red Angus.

What once took years to accomplish was done within a matter of months with fewer samples.

Scientists were able to develop a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test and have it available to breeders in less than a year. They also determined that the popular bull was not a carrier, to the relief of the industry.

“The mutation had crept into the pedigree of the offspring of the bull by his mating with a carrier heifer,” Smith says.

Scientists looked at the genetic makeup of more than 450 normal Red Angus to see how common the mutation might be in the breed. No healthy animals were found to be homozygous for the mutation, consistent with the prediction that all animals with two copies of the mutation should be affected. More than 570 Black Angus bulls were also tested and found to be negative for the osteopetrosis-causing mutation.

Breeders now have a test they can use to manage the defect, identify cattle that may be carriers, and make decisions on whether the animal’s other traits make it valuable enough to continue using for breeding, Smith says. This way, the bone disease can be eliminated from the herd without sacrificing other genetic progress made during development of the breed.

“What’s really important is that with the rapid response time with which we can now put a test like this into the hands of producers, they don’t have to be as afraid of genetic defects anymore,” Smith says. “We can create tests relatively fast now and prevent these kinds of diseases from spreading throughout the herd.”

The newly developed PCR test—provided through RAAA—has been widely used and is required for registration of most Red Angus.

“If it had not been for the research team, we would not have this tool to provide to our customers in their ongoing quest to develop those reliable genetics,” Keenan says. “The Red Angus Association is grateful for that.”—By Sandra Avant, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Food Animal Production (#101), an ARS national program described at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

To reach scientists mentioned in this article, contact Sandra Avant, USDA-ARS Information Staff, 5601 Sunnyside Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705-5129; (301) 504-1627.

"New Test Detects Bone Disease in Red Angus" was published in the September 2011 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.