Federal Forests Still Protecting

Chesapeake Bay After 100 Years

|

|

For 100 years, the Henry A. Wallace Beltsville Agricultural Research Center (BARC) in Beltsville, Maryland, has maintained and protected its share of 25,660 acres of green space just 15 miles from the nation’s capital.

The expanse of green space, sometimes called the “Green Wedge,” owes its existence to the fact that most of it has been in federal hands since before 1940. BARC was the first federal landowner, beginning with about 500 acres in 1910.

A 2009 Executive order on the Chesapeake Bay—calling for increased cooperation between federal, state, and local agencies and organizations—finds BARC once again at the forefront of environmentally and fiscally responsible cooperative land-use decisions affecting this vast open space.

This cooperation began formally in 2006 with the signing of an agreement with three other major landowners—the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Patuxent Research Refuge, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Goddard Space Flight Center, and the U.S. Army’s Fort George G. Meade—as well as the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the nonprofit Center for Chesapeake Communities, officially forming the Baltimore-Washington Partners for Forest Stewardship. That same year, ARS’s Beltsville Area Office signed a similar agreement with the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

The Bay’s Lungs and Kidneys

Over the years, BARC grew, but ceded about half of its land to other agencies, including the U.S. Departments of State, Treasury, and the Interior, and NASA—leaving BARC with 6,615 acres today. But most of the green space has been left intact—virtually as it was in 1910.

The Green Wedge is a national treasure, the largest expanse of continuous deciduous forest remaining between Norfolk, Virginia, and Boston, Massachusetts. It serves as the lungs and kidneys for the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area in the bay’s watershed, with vegetation and wetlands that filter out pollutants. BARC streams deliver clean water to the bay. In fact, Upper Beaverdam Creek, on BARC land, sets state standards for clean water. One of the many ways the partnership keeps these waters so clean is by planting trees along the streambanks as buffers.

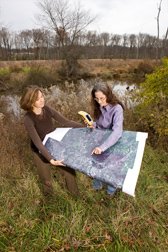

The partners encourage collaborative solutions to shared challenges by bringing together scientists from the different agencies that share the Green Wedge. For example, Megan Lang, a USDA Forest Service ecologist stationed at BARC, and Molly Brown, a scientist at NASA-Goddard, work together to offer remote-sensing tools to land managers within the Green Wedge.

Another example is joint pest-control efforts. A few years ago, Patuxent, Goddard, and three other federal agencies joined BARC in using a biological insecticide, GYPCHEK, to protect oak trees from gypsy moths. The Forest Service developed GYPCHEK, and ARS scientists did research seeking improved efficiency in producing the naturally occurring virus strain that is its active ingredient.

David Prevar, the ARS Beltsville area safety and health manager, says that threats such as gypsy moths “do not respect property lines, so it pays for landowners to work together.”

The Green Wedge’s Historical Forests

A BARC ecology committee has been protecting the Green Wedge since 1977. Through this committee, scientists worked to have forests on this land designated as research forests to reflect their historical and continuing contributions to protecting wildlife and the Chesapeake Bay. The honor also reflects the historic cooperative research done by the Patuxent Research Refuge and ARS scientists for the benefit of wildlife habitat. Patuxent scientists have developed techniques for monitoring wildlife, such as spotted salamanders and other amphibians, on BARC as well as Patuxent lands.

About 1990, BARC switched to sustainable farm-operation practices to reduce pesticide use and erosion losses. These changes were based on the results of BARC research.

In 1996, BARC voluntarily began a nutrient-management plan—5 years before the State of Maryland required this for private farms—to keep nitrogen and phosphorus out of the Chesapeake Bay. Studying an experimental watershed on BARC, ARS soil scientist Greg McCarty determined ways to improve the effectiveness of vegetative riparian buffers to filter out nutrients and pesticides before they reach the bay. Again, BARC scientists developed these practices, through research, to serve as a model for bay-area farmers.

A Green Way To Cap an Old Landfill

From 2003 through 2008, Prevar, working with ARS microbiologist Pat Millner, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and private consultants, designed and conducted a pilot study for an alternative vegetative capping method on part of a 30-acre municipal landfill located at BARC.

The Maryland Department of the Environment has been following this project closely, since there are numerous landfills statewide that would benefit from this alternative closure approach. Vegetative caps for landfills, rather than traditional clay caps, are gaining acceptance from state agencies as a sustainable practice, and EPA sees the BARC project as a potential model. This method of capping is more environmentally sound and economical, and, if accepted by Maryland, would provide the added benefit of creating more than 30 acres of forest canopy and critical habitat when fully implemented.

“As part of the vegetative capping design, Pat has come up with a novel way to reduce methane emissions while preventing rainfall from penetrating into the municipal waste and then leaching into groundwater,” Prevar says. “Also, an increase in forest canopy contributes to improving the bay’s health by sequestering carbon and filtering runoff.”

The Next 100 Years

As though in repayment for the research and stewardship, the lands constantly reveal new surprises, such as globally rare forms of plants and wildlife—including a new bee species, a surprising number of dragonfly species, 141 rare plant species, including two species of orchids, and rare plant communities such as magnolia bogs and pine barrens.

“These natural resources expand our research opportunities and demonstrate the importance of inventorying and preserving important ecological resources beyond our 100th anniversary,” Prevar says.

This research supports the USDA priority of responding to climate change.—By Don Comis, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Manure and Byproduct Utilization (#206), Water Availability and Watershed Management (#211), Agricultural System Competitiveness and Sustainability (#216), and Crop Protection and Quarantine (#304), four ARS national programs described at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

David A. Prevar and Patricia D. Millner are with the USDA-ARS Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, 10300 Baltimore Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705; (301) 504-5557 [Prevar], (301) 504-5631 [Millner].

"Federal Forests Still Protecting Chesapeake Bay After 100 Years" was published in the February 2011 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.