Marvelous Microbe Collections Accelerate

Discoveries To Protect People, Plants—and More!

|

|

If you’re a contact lens wearer, you probably remember headlines a few years ago about emergence of a worldwide medical problem—molds that live on contact lenses and cause debilitating eye infections.

What you may not have known: ARS experts at the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research in Peoria, Illinois, did the detective work necessary to precisely identify these molds—which turned out to be Fusarium species.

These researchers derived the correct identification by working with a database of distinctive Fusarium genetic material that can be used to reliably differentiate among the many Fusarium species that cause disease.

In turn, this handy database owes part of its origin to the exemplary collection of hundreds of species of Fusarium housed at Peoria in the ARS Culture Collection.

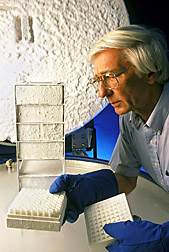

Research leader and microbiologist Cletus Kurtzman and colleagues curate this comprehensive assemblage of living specimens of harmful and helpful bacteria, molds, actinomycetes (such as antibiotic-producing Streptomyces), and yeasts from around the planet.

|

|

Proximity to this genebank—the world’s largest publicly accessible collection of microbes—has, not unexpectedly, hastened discoveries by Peoria scientists. Their accomplishments include innovative new ways to detect, identify, classify (put in the correct family tree), and newly use these microorganisms to make foods safer, protect plants from pests, and create new industrial products.

Of course, other scientists also benefit. Some 4,000 strains of microbes are shipped each year from this flagship collection to researchers elsewhere.

Such sharing of specimens is all in a day’s work at other specialized ARS microbe collections as well, including the U.S. National Fungus Collections in Beltsville, Maryland.

With more than 1 million dried specimens, these collections are the largest of their kind, according to director Amy R. Rossman. Scientists worldwide use them as a reference, and specimens are loaned for research projects.

Recent additions to the collections include seven species of fungi in the chestnut blight group that were discovered and described in the past few years. These descriptions will be used by forest pathologists to determine which species of fungi occur on hardwood trees, making it easier for these specialists to figure out how best to treat infected trees.

|

|

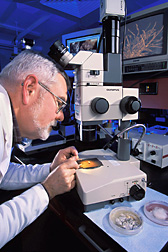

Fungi that cause plant diseases are the primary focus of the U.S. National Fungus Collections. That’s in contrast to another fungal genebank, the ARS Collection of Entomopathogenic Fungal Cultures, which specializes in live fungi that attack or in other ways affect insects, spiders, mites, and other invertebrates. ARS microbiologist Richard Humber is curator of this Ithaca, New York-based collection. Humber and Beltsville coinvestigators Stephen Rehner, an ARS molecular biologist, and Joe Bischoff, a mycologist with USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, have evaluated hundreds of isolates from the collection’s holdings to make crucial molecular revisions of the taxonomy of two important fungal species. They are Beauveria bassiana, used to control termites, for instance, and Metarhizium anisopliae, which serves as a biological insecticide that controls termites, thrips, and grasshoppers.

There’s more. ARS microbiologist Peter van Berkum, also at Beltsville, directs the National Rhizobium Germplasm Resource Collection. Rhizobium is the scientific term for bacteria that can form a symbiosis with alfalfa, soybean, and other legumes to provide these plants with a source of fertilizer—ammonia—for growth and reproduction. This is done by a process known as “biological nitrogen fixation”—the reduction of nitrogen gas from the atmosphere into ammonia. The collection provides a germplasm resource for industry to use in manufacturing inoculants and for researchers to use in investigating symbiosis and nitrogen fixation.

|

|

Current projects involving the collection include genetic mapping of Rhizobium found in association with alfalfa and other Medicago species from Egypt, Spain, and Tunisia. Also under way: Genetic mapping of Bradyrhizobium populations found in association with soybean. This investigation may determine—among other things—whether the Bradyrhizobium in U.S. soils are the same as those in the Far East, soybean’s place of origin.

Both projects may lead to new ways to boost plants’ productivity without using fertilizer.—By Marcia Wood and Alfredo Flores, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Plant Diseases (#303), Crop Protection and Quarantine (#304), and Plant Genetic Resources, Genomics, and Genetic Improvement (#301), three ARS national programs described at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

To reach scientists mentioned in this article, contact Marcia Wood, USDA-ARS Information Staff, 5601 Sunnyside Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705; (301) 504-1662.

|

|

Troublesome Microbes That Resist Antimicrobials

The Antimicrobial Resistance Collection

In an effort to monitor pathogenic microbes’ resistance to antimicrobials, the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) was established in 1996 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Veterinary Medicine in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

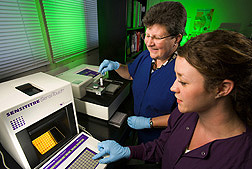

The animal component of NARMS focuses on zoonotic pathogens (those that can be transferred from livestock or wildlife to humans) and is housed within ARS’s Bacterial Epidemiology and Antimicrobial Resistance Research Unit. Led by microbiologist Paula Cray, the unit is part of the ARS Richard B. Russell Research Center in Athens, Georgia.

The NARMS animal component tests samples, or isolates, obtained from healthy on-farm animals, animals being diagnosed for illness, and food animals at slaughter. The specimens are stored in the Antimicrobial Resistance Collection, maintained by Cray’s team.

Resistance of Salmonella, Campylobacter, Enterococcus, and Escherichia coli to antimicrobials such as streptomycin and tetracycline is tested, monitored, and tracked in an attempt to better understand foodborne pathogens’ resistance trends.

“Nontyphoid Salmonella was chosen as a sentinel organism of NARMS’s animal component, which was launched in 1997,” says Cray. A sentinel organism is one used to track changes in resistance over time. “Testing of Campylobacter isolates began in 1998, while E. coli was included in 2000. Enterococcus testing has also been added to the data set.

“It is vital that we track these trends of resistance and disseminate the information to animal producers, veterinarians, and consumers.”—By Sharon Durham, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

Paula Cray is in the USDA-ARS Bacterial Epidemiology and Antimicrobial Resistance Research Unit, Richard B. Russell Research Center, 950 College Station Rd., Athens, GA 30605; (706) 546-3685.

"Marvelous Microbe Collections Accelerate Discoveries To Protect People, Plants—and More!" was published in the January 2010 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.