A Better Way To Spot Eggshell Cracks

Nobody wants to buy a carton of eggs only to find that some are cracked. So naturally cracks are a key factor in processing and grading table eggs. But some cracks, called “microcracks,” are so small that even an experienced human grader’s eye can miss them at the processing plant. Unfortunately, the microcracks grow over time and are often easily visible by the time they reach consumers at market.

Cracks are a food-safety concern because they can allow contamination of the egg by pathogens, such as Salmonella. Fortunately, safety procedures for eggs begin long before the consumer buys a carton.

The USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS), which regulates eggs, needed a more objective method to detect microcracks—one that is simple and inexpensive and works in a batch system. They turned to Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientists for a solution.

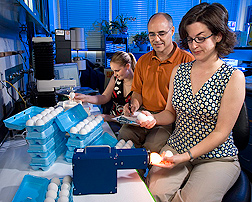

The ARS team included food technologist Deana Jones, at the Egg Safety and Quality Research Unit, and engineers Kurt Lawrence, Seung Chul Yoon, and Bosoon Park, image analyst Jerry Heitschmidt, and technician Allan Savage, at the Quality and Safety Assessment Research Unit. They designed and built a device that helps find those hard-to-see cracks. Both research units are part of the Richard B. Russell Research Center in Athens, Georgia. A patent application for the technology has been filed.

|

|

The Old Way’s the Hard Way

Currently, many high-speed egg-processing plants use high-frequency analysis to “listen” for cracks, says Lawrence. Other plants still do it the old-fashioned way, with human graders visually inspecting eggs with a bright light source in a low-light environment.

It is impossible to detect all cracks, so a few are always missed; but the problem is that no method picks up the microcracks. The result is that some cartons—by the time they get to market—may have eggs with too many cracks. Another problem is that current methods may unnecessarily remove eggs that are thought to be cracked but really aren’t—what scientists call a “false positive.”

Advances in modern egg-grading machines have resulted in the processing of up to 180,000 table eggs per hour. Processing plants that operate under USDA grading certification practices are required to have a certain portion of their eggs graded by AMS human graders. In the largest plants, the limiting factor for processing speed is the grader—so there’s a need for a second person to handle the volume.

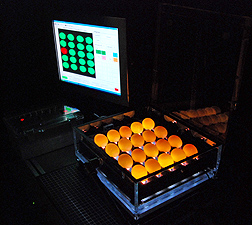

With this in mind, the ARS researchers developed a new technology that allows tiny cracks to be more obvious. It can also spot other blemishes on an egg that are assumed to be cracks but really aren’t. The technology uses a pressure chamber and an imaging system that makes even the tiniest fractures more apparent.

Technology Emulates Human Graders

The idea is based on one of the basic methods human graders use to identify egg cracks: They gently tap two eggs together and listen for a dull sound. “This technique relies on the acoustic properties of the egg. In other words, a cracked egg makes a different sound that an intact one,” says Jones.

The second method is simply to visually inspect the egg for a crack. “If there’s a feature that looks like it might be a crack or if the grader hears the indicative sound of a cracked egg, they’ll press and/or squeeze the egg to help confirm the presence of a crack,” Jones explains.

Initial research with an imaging system tried to emulate the visual inspection. But too many noncrack shell features were perceived as cracks, leading to numerous false positives. So the researchers needed a method to enhance cracks—similar to the way human graders squeeze the egg along the crack to see if it opens. “The question for us then became how to automatically press along a crack that can be located anywhere on an egg shell and in any orientation,” says Lawrence.

Further engineering research was in order. It was at that point the scientists realized that the wrong question was being asked—or rather, the answer didn’t fit the question. The detection system could not press or squeeze the egg like the graders did, but what would happen if they could pull on the egg with a slight negative pressure, or vacuum?

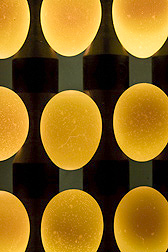

It was like a lightning bolt of inspiration—and that’s what a crack looks like to the camera when it opens under pressure. The first prototype chamber was built for a single egg, but the scientist quickly expanded it to a 20-egg chamber.

To test the chamber, 1,000 white-shell table eggs were obtained from a nearby egg-processing facility, transported to the laboratory, and brought to room temperature to simulate processing conditions. Many of the eggs were manipulated to cause microcracks and were immediately examined by AMS graders and scored as either intact or cracked. The eggs were then subjected to the negative pressure/imaging system and regraded.

The results were surprising. “The system detected 99.4 percent of the eggshell cracks while recording almost no false positives—0.3 percent—for an overall accuracy of 99.6 percent. In comparison, the professional human graders had 85.8 percent crack detection and 1.2 percent false positives, with an overall accuracy of 94.2 percent on these hard-to-see microcracked eggs,” Lawrence says. “The system’s results are much better than anyone had achieved earlier.

“This could very well provide a tool that egg graders can use to consistently identify cracked eggs and improve the quality of the eggs that reach the consumer.”—By Sharon Durham, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Food Safety, an ARS national program (#108) described on the World Wide Web at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

Kurt Lawrence is in the USDA-ARS Quality and Safety Assessment Research Unit, Richard B. Russell Research Center, 950 College Station Rd., Athens, GA 30605; phone (706) 546-3527, fax (706) 546-3607.

Deana Jones is in the USDA-ARS Egg Safety and Quality Research Unit, Richard B. Russell Research Center, 950 College Station Rd., Athens, GA 30605; phone (706) 546-3486, fax (706) 546-3035.

"A Better Way To Spot Eggshell Cracks" was published in the February 2009 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.