Seeds of Knowledge

New online guide helps identify the world’s seeds and fruits.

If there’s a perfect entity in nature, it would have to be seeds.

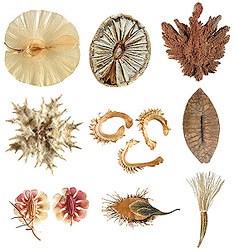

These compact packages—in an astounding array of sizes, shapes, colors, and textures—contain all the reproductive material a plant needs for making hundreds, if not thousands, more of itself.

With their streamlined anatomy and assortment of hooks, spurs, burs, and barbs that even the most inventive engineers couldn’t have dreamed up, seeds are capable of journeying hundreds and even thousands of miles. Think of cockleburs that latch onto a rabbit’s fur or a hiker’s socks. Or maple tree “flippers” parachuting down through the treetops. Or dandelion fluff blowing in the wind.

But not everyone’s applauding these efficient voyagers. That’s because some plant species—which are typically well behaved in their home territories—can trigger ecological chaos in other environments. For instance, spotted knapweed, leafy spurge, and garlic mustard, to name a few, have all invaded U.S. lands, displacing thousands of acres of native vegetation that people, livestock, and wildlife depend on.

Federal inspectors are at the front lines of the battle against these invasives. Stationed at ports around the country, they stand ready to screen incoming plant materials for possible unwanted stowaways. But trying to identify hundreds of unusual seeds and fruits—from as far away as Asia, Australia, or Central and South America—is a daunting task.

That’s why seed experts—systematists with the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Beltsville, Maryland—play such an important support role in helping to prevent entry of damaging weeds into the country. These researchers may be called on by other agencies, such as the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, to help identify strange and suspicious seeds, fruits, and fungi.

A Vital Service

Last year, scientists who work at ARS’s Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory (SBML) in Beltsville helped federal and state agencies identify about 200 mystery seeds and fruits.

This service is invaluable, says the laboratory’s research leader Amy Rossman, who is also an expert at identifying fungi. “Invasive plants, just like most crop plants, travel around as seeds,” she says. “So being able to identify them quickly and accurately is probably one of the most simple and cost-effective ways to keep them out of the country.”

And SBML researchers, including botanist Joseph Kirkbride, have had their share of run-ins with troublesome weeds and plants.

One of the plant groups he says inspectors commonly encounter are members of the spurge family. Leafy spurge, which has invaded several states in the West, is a serious target of land managers and federal and state agencies concerned about the plant’s rippling effects on native flora and fauna.

And surprisingly, the plant genus Solanum, which gives us such favorites as the potato and tomato, is also the source of many nuisance weeds. In fact, a member of the nightshade group, the wetland nightshade, is invading southern Florida’s fragile wetland areas at an alarming rate.

“What makes some plants so great from an agricultural standpoint—that is, their prolific and efficient seed production—is also what makes related weeds so hard to control,” says Kirkbride.

And invasives aren’t all there is to worry about. Some eye-catching seeds and fruits that people may bring back with them from overseas travels are poisonous.

“For instance, the scarlet-colored seed produced by a member of the Abrus genus—which is known as the ‘rosary pea’ or ‘crab’s eye’—is often used for making necklaces and rosary beads in other countries,” says Kirkbride. “But they’re fatal if eaten.”

Tedious and Painstaking Work

Trying to identify the world’s numerous seeds isn’t like strolling through the garden to note the names of its flowers.

To do it right, and as swiftly as possible, ARS systematists tackle their mystery subjects armed with microscopes, identification guides and booklets, and a collection of thousands of seed and fruit samples for reference.

For example, consider legumes—the family that gives us peas, peanuts, soybeans, and lentils.

Right now, taxonomists organize this group’s widely varying and numerous members into 650 genera, or groups of related species. Sometimes, though, one or two subtle features may be all there is to help distinguish between two legume species.

When researchers analyze a legume seed under a microscope, they usually study the embryo inside. “If we happen to see microscopic hairs growing on this tiny embryo,” says Kirkbride, “we’re likely to get pretty excited. That’s because, by finding those little hairs, we know we can rule out over 16,000 legume species. Only five legumes are known to have them.”

To help make identification go as smoothly as possible, ARS’s Kirkbride and colleagues have developed an online database for helping port inspectors, researchers, and others identify seeds and fruits that stump them.

“This new database should at least shrink the universe a little, in terms of the countless seeds and fruits out there,” says Kirkbride. “Most seeds look pretty uniform to people, so we hope our tool can ease some of the difficulty that comes with tedious identification.”—By Erin K. Peabody, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Plant Genetic Resources, Genomics, and Genetic Improvement, an ARS National Program (#301) described on the World Wide Web at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

Amy Y. Rossman and Joseph H. Kirkbride are with the USDA-ARS Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, 10300 Baltimore Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705-2350; phone (301) 504-5364 [Rossman], (301) 504-9447 [Kirkbride], fax (301) 504-5810.

Name That Seed!

When it comes to seeds, you can’t say, “seen one, seen ‘em all.” In fact, as Joseph Kirkbride, an ARS botanist in Beltsville, Maryland, knows, there’s incredible diversity among them. For instance, the world’s smallest seeds, produced by orchids, can’t be seen with the naked eye. “The heftiest come from rainforest-dwelling legumes and can weigh close to 2 pounds,” he adds.

An expert on seeds and fruits, Kirkbride works at the agency’s Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory in Beltsville. He’s also director of the U.S. National Seed Herbarium, which is housed there.

The seeds he looks after are carefully tucked inside vials, envelopes, and boxes filed inside hundreds of drawers. They represent 390 families, 13,000 genera, and over 27,000 species. Finding a seed is like hunting down a book in a library: They’re organized alphabetically according to the family or genus they belong to.

But the collection is more than just an archive or museum. “We’re always using the collection for research purposes and for help in identifying unusual seeds,” says Kirkbride. Recently, many of the herbarium’s thousands of seeds and fruits were taken out of their drawers. One by one, each was carefully scrutinized, sketched, and photographed.

Why? Kirkbride and colleagues have spent the last 5 years compiling an online database that will help inspectors identify seeds and fruits that have hitched rides into the country—in shipments of grain, horticultural plants, and other plant cargo. It will also serve as a tool for researchers studying ecology and biology.

This first-of-its-kind online resource is called “The Family Guide for Fruits and Seeds.” To access it, go to http://nt.ars-grin.gov/sbmlweb/onlineresources/frsdfam/.

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) agents will be able to use the new guide for identifying strange and unusual seeds—making it easier to prevent noxious plants from entering the country.

The database includes all 418 plant families that produce either fruits or seeds. While many fruits just so happen to be deliciously edible, those beauties are really just a fleshy carapace for housing plant seeds.

Along with unwanted seeds, our most important foods—rice, wheat, and corn—are also represented in the database, since these vital plants all sprout from some sort of seed.

More than 3,000 photos, taken by APHIS technician Robert Gibbons, illustrate the great diversity of seeds. Many had to be magnified more than 100 times for their delicate features to come into focus.—By Erin K. Peabody, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

"Seeds of Knowledge" was published in the March 2007 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.