ARS Is Banking on Germplasm |

|

A display of seeds from the late 1890s at the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation that typifies the crops grown in the North Dakota area at that time. (K10190-1) |

The main functions of banks are to hold depositors' money safely, to lend some of that money to others, and to invest for the future. The Agricultural Research Service operates its own network of "banks" that make up the National Plant Germplasm System. But instead of money, the 20 repositories and support units that make up the system hold germplasm for scientists to study, for breeders to grow, and for land managers to use. "Germplasm" refers to the parts of plants and animals that are needed for reproduction, like seeds or semen. ARS wants to maintain genetic diversity in plants and animals collected from around the world—particularly populations that are dying out or are no longer available because of greater restrictions in international germplasm exchange. About an hour's drive north of Denver on the campus of Colorado State University is the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation (NCGRP), formerly known as the National Seed Storage Laboratory—the central bank of the system. Nearly half a million samples of germplasm are stored on four floors, similar to safe deposit boxes at neighborhood banks. Each of the 19 other repositories contains certain species of plants, while this one contains backup versions of them all and is the only one that stores animal germplasm. |

National Animal Germplasm Program coordinator Harvey Blackburn and technician Ginny Schmit place germplasm samples into a liquid nitrogen tank for long-term storage. (K10187-1) |

The Fort Collins, Colorado, facility receives germplasm from ARS scientists or other researchers and sometimes from private individuals who have unique or old germplasm. Scientists from outside the United States also deposit samples into the collection. Other researchers withdraw samples to develop cultivars or to study the species. "We are one of the largest, most effective genebanks in the world," says NCGRP director Henry L. Shands. Even under the best storage conditions science can provide, germplasm does not survive forever, and ARS scientists are trying to develop ways to preserve it longer. Genebanks must periodically have the collections grown out and fresh germplasm harvested to place back in the collection. |

Plant physiologist Loren Wiesner (right) and technician Bill Prange retrieve seed samples from this -18° C (0° F) storage vault for distribution to NCGRP sites for cultivar development and study of the species. (K10189-9) |

A Billion Seeds . . . and Growing The center's plant focus is divided into two areas: the Seed Viability and Storage Research Unit, run by plant physiologist Loren E. Wiesner, and the Plant Germplasm Preservation Research Unit, run by plant physiologist Christina T. Walters. Wiesner's job is to document and preserve seeds and vegetatively propagated germplasm for long-term storage as well as to determine the quality of the seeds. He is also responsible for distributing the germplasm to the other repositories and sometimes to researchers and breeders. Walters and her scientific staff represent one of the few genebanks worldwide conducting research on how these types of facilities can collect and store germplasm more efficiently. Seeds at the NCGRP are stored at either –18° C (0° F) or –150° C (–238° F). Liquid nitrogen (LN) storage provides the lower of these two temperatures. LN storage slows deterioration and gives seeds longer lifespans, but it is more expensive to use. Seeds that survive well at –18° C do not need to be placed in LN, but seeds that have shorter lifespans or are exceedingly valuable are placed at these very low temperatures for safekeeping. Some plant germplasm must be stored at LN temperatures to prevent ice from forming in cells. |

Using an incubator, plant physiologist Christina Walters measures how fast seeds age at high temperatures and relates this to how long they will survive in cold storage. (K10188-1) |

Before storage, Wiesner has the technicians test the seeds for viability and optimum moisture content. Seeds to be stored at –18° C are put into standardized moisture-proof, plastic-lined foil bags and then heat-sealed. A sample of seeds for LN storage is exposed to LN vapor for 24 hours, and then germination is compared to that of unexposed seeds. If there is a 10-percent decrease in the exposed group compared to the control group, then the seeds are stored at –18° C rather than in LN. The seeds that Wiesner places in LN are first placed in plastic tubes consistent with the seed size and then put in the LN tanks. About 10,000 square feet are reserved for LN storage and 7,500 square feet for the –18° C storage, but the –18° C storage area will need to be increased in the near future to handle the demands for security backup storage. Storing seeds at –18° C or in LN stresses them. Walters and her staff look for ways to reduce that stress or to fix the damage. They have found that seeds from tropical areas contain a lot of water or have unusual lipids, and this makes them damage easily. An example is Cuphea, which comes from Latin America and is valued in the food industry for its medium-chain fatty acids (8 to 14 carbons rather than the usual 16- or 18-carbon fatty acids). Some Cuphea seeds were killed when stored at –18° C, but damage can be averted by warming them in an incubator before they are germinated. Walters reasoned that it was like olive oil left in a refrigerator; the oil has to melt before you can mix it with vinegar. |

Seeds from domestic crops (inner circle) are usually larger, lighter in color, and more uniform than their wild relatives. Clockwise from top: Peanuts, corn, rice, coffee, soybean, hops, pistachio, and sorghum. (K10192-2) |

Another new aspect of the NCGRP research is the work on plants native to U.S. rangelands. "These plants are used to restore rangelands that have been devastated by fire, and so far there is no program in the United States to ensure that we have the plants we need," Walters says. Most crops grown in the United States actually originated abroad, brought by immigrants from their native countries. But the United States still has a lot of native plants that are useful, and ARS is trying to collect them. Walters points out that many of the native plants produce medicines, including one they studied that has been shown to help breast cancer patients. Preserving plants collected from the wild, like U.S. native species, is more difficult than preserving crop seeds. Plants in the wild look and behave differently, growing at different rates and flowering at different times. The challenge to preserve these plants may be well worth it, since they are a future source of genes that will make crops more resistant to diseases, insects, and extreme weather. |

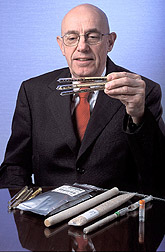

Center director Henry Shands holds glass tubes from one of the oldest experiments testing seed longevity, begun in 1948. On the table are samples of containers used to store germplasm, including heat-sealed foil bags for storage at -18°C and polypropylene tubes for storage in liquid nitrogen. (K10189-1) |

The Animal Collection Is Taking Off ARS' storage of animal germplasm is relatively new. A congressional mandate called for the National Animal Germplasm Program (NAGP) to be part of the whole germplasm system. In 1999, a task force suggested the program be located within the National Seed Storage Laboratory in order to share some of the same infrastructure. Animal scientist Harvey D. Blackburn, who is in charge of the NAGP, helped to usher in the first germplasm entry of 40 chicken lines in 2000. Since then, germplasm has been added from various breeds of dairy and beef cattle, sheep, goats, and swine. They are also starting an aquaculture collection with striped bass and catfish germplasm. While the NAGP is run by ARS, more than 70 scientists are part of the program. Many of them come from industry and universities as well as from other government agencies. They make up the committees (swine, dairy, beef, poultry, aquaculture, and small ruminants) that help decide what breeds and lines within breeds should be added to the collection. There is also a technical committee that advises on proper storage techniques. At any one time, Blackburn is engaged in numerous projects that are as unique as the animals he studies. For example, he is working with the ARS Germplasm and Gamete Physiology Laboratory in Beltsville, Maryland, on storage and transportation methods for boar semen. "We are trying to find ways to better protect the cells during transport and processing," Blackburn explains. Though the animal program is new, it has acquired older germplasm. The collection contains semen from Hereford and Limousin bulls from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. The repository has also acquired semen from a Holstein population founded in the 1960s. "This older material is critical because it helps broaden the genetic base in the collection, and it will be used to evaluate changes in a breed's genetic composition over time," Blackburn says. In the future, Blackburn wants to acquire more species as well as increase the number of breeds representing species he already has. The NCGRP is renovating to provide more space for animal germplasm collection and research, in addition to acquiring new analytical instrumentation.—By David Elstein, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff. This research is part of Plant, Microbial, and Insect Genetic Resources, Genomics and Genetic Improvement (#301) and of Food Animal Production (#101), two ARS National Programs described on the World Wide Web at http://www.nps.ars.usda.gov. Henry L. Shands, Loren E. Wiesner, Christina T. Walters, and Harvey D. Blackburn are with the USDA-ARS National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation, 1111 South Mason, Fort Collins, CO 80521; phone (970) 495-3200, fax (970) 221-1427. "ARS Is Banking on Germplasm" was published in the February 2003 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.

|