Ouch! The Fire Ant Saga Continues

The latest news in the world of fire ants: The tiny pests with a ferocious sting are spreading. Until recently, red imported fire ants occupied more than 300 million acres in 12 southern states and Puerto Rico. Now they've become established in California and New Mexico.

As the ants spread, the race to stop them is even more intense for a team of Agricultural Research Service scientists at Gainesville, Florida. There, researchers at ARS' Center for Medical, Agricultural, and Veterinary Entomology are seeking new ways to keep this pest in check.

"Our goal is to try to reduce their numbers so native ant species can compete," says entomologist David F. Williams. He is the lead scientist on the fire ant biocontrol project in the center's Imported Fire Ants and Household Insects Research Unit that is headed by Richard J. Brenner.

Fire ants are thought to have spread to the United States from their native South America via contaminated ships in the early 1930s. Since then, their spread has been slow but steady. "We believe imported fire ants have flourished in the United States because they have no natural enemies here. We're trying to change that by working with state cooperators to introduce natural enemies," Williams says.

ARS and representatives from the Council of State Governments' Southern Legislative Conference initiated a National Fire Ant Strategy in 1998 to help tackle the fire ant problem. One of the group's objectives is to reduce pesticide use by substituting biological controls. In the past 2 years, ARS scientists have dispatched new artillery to help control fire ants: a slow-acting disease and a decapitating fly.

Microbial Combatants on the Move

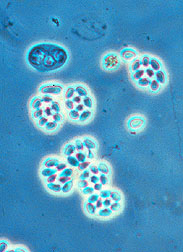

Thelohania solenopsae, a microorganism from South America, infects fire ant colonies and causes disease. Williams says workers probably transfer the pathogen to the queen through food exchange. As the disease slowly reduces her weight, she lays fewer and fewer eggs, and all are infected with the pathogen, further weakening the colony.

Williams says colonies generally die within 9 to 18 months. However, in lab studies, he found that after 3 months the infected colonies were smaller than healthy ones. The microorganism doesn't harm plants or native ant species. And after years of testing, it's been found only in red and black imported fire ants.

Williams works closely with ARS' South American Biological Control Laboratory in Buenos Aires, Argentina, to get this and other biological controls through quarantine and into the United States. Natural enemies of imported fire ants are also native to South America.

|

|

In 1996, the scientists discovered that the Thelohania pathogen wasn't confined to its native land, but had already infested fire ant colonies in Florida, Mississippi, and Texas. This opened the door for releases in Florida, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, North and South Carolina, Alabama, and Georgia.

"Since our first release in 1998 in Florida, Thelohania has spread to more than 75 percent of the colonies we're monitoring," says Williams. "But it will take longer to see a major impact."

Entomologist David H. Oi, who works with Williams on evaluating Thelohania and other biological controls, says they know the organism kills the colonies. "But we want to see how it is passed to the queen. This is one of few microbial agents that infect mated queens and pass on to her eggs," says Oi.

"We want to find out if infected virgin queens can mate and then spread the disease to their offspring. If so, this will be a natural way to distribute Thelohania, besides introducing infected brood into existing colonies," says Oi. The scientists hope to get the answer in a study they will start this year.

|

|

Even more powerful than Thelohania is another pathogen called Vairimorpha, which Williams says is not that different. When combined with Thelohania, it kills colonies in 2 to 6 weeks. "The problem is, about 20 percent of fire ant colonies in South America contain Thelohania, but only 1 percent contain Vairimorpha," Williams says. "It's so rare, hard to find, and also hard to keep alive to study. There's a lot we don't know about it, but we're excited about finding out."

Insect Snipers

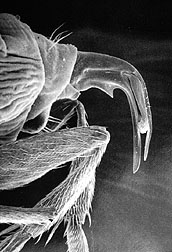

Another line of defense that "has fire ants literally on the run is the phorid fly, Pseudacteon tricuspus, their mortal enemies," says ARS entomologist Sanford D. Porter. "The ants will run and hide, freeze, stop foraging, or twist upside down so the flies don't sting them. The only way they could have evolved these defensive behaviors is if the flies had some effect on fire ant populations."

The phorid flies hover over the fire ant mound, then zoom in to pierce an ant's outer cuticle and deposit an egg underneath. The egg quickly hatches into a fly maggot, or larva, that moves into the ant's head. When the maggot is mature, it releases an enzyme that causes the ant's head to fall off—decapitation. Using the ant's head as a safe hideaway, the fly completes its development inside.

"One female phorid fly usually contains a hundred or more torpedo-shaped eggs, so she can make multiple attacks," says Porter. Porter released thousands of the tiny flies in July 1997 in Gainesville. Since then, he's released them in Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Alabama." The exciting part is that the Brazilian parasitic flies released in Florida have survived for nearly 2 years. They've gone through many generations and appear to be permanently established," says Porter. "Fly populations are still growing, so it may take 1 to 2 years before they have a noticeable impact."

What's next? "We have a new, smaller phorid fly species, Pseudacteon curvatus, which will attack smaller-sized fire ants," Porter says. "We have found at least 20 species of phorids in South America that specifically attack fire ants."

|

|

Porter says this new species is even better, since scientists can rear it more easily. He has completed host-specificity tests and is planning on seeking permission to field-test P. curvatus. They have tested the flies with different foods, animal dung, and human waste to ensure they're not attracted to anything other than fire ants. He says the flies aren't visible unless you kick over a fire ant mound.The scientists are hoping these two flies and other natural enemies will eventually tip the ecological balance against fire ants in the United States, so they will no longer be the dominant species. Fire ant populations are greater here than in South America, where natural enemies appear to keep them in check.

Still waiting to be called to duty is Solenopsis daguerrei, a parasitic ant discovered in Argentina in 1930. This ant is unusual because it produces no workers. Williams says the Solenopsis queen uses her mandibles to clamp onto a fire ant queen's body. Like a wolf in sheep's clothing, the parasitic ant queen chemically disguises herself, mimicking the natural attractants of the fire ant colony; otherwise, she would be killed. The fire ant queen becomes debilitated and lays fewer eggs, weakening the colony. Williams says they are still trying to learn more about S. daguerrei.

|

|

Tracking the Enemy

It would also help scientists if they could find out where fire ants may start new colonies. Entomologist Dana A. Focks, an expert on computer modeling, is working on that. He's focusing on when and where winged ants, called alates, mate and start new colonies.

"No really good models exist that can predict where alate flights might have occurred or could possibly occur," says Focks. "We want to build a satellite-based program to find if one has taken place."

Mating depends on temperature and weather, but most fire ants emerge in warm weather after rainfall. Focks is working on a cooperative grant project with IBM, Inc., Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to develop a tracking system that can predict when alates have emerged or will emerge.

Focks says this will ultimately save money for nurserymen who typically have to treat their plants and surrounding areas with insecticides to ensure they don't transport ants from infested areas to noninfested ones. They generally do this before shipment.

"We're hoping that in the future a person can go to the Internet and get site-specific information on whether a flight occurred, based on weather conditions, temperature, and other information. Nurserymen could use this information to keep from re-treating their stock unnecessarily," Focks says.

Attacks on Animals

Another growing problem with fire ants is their ecological impact, especially on endangered vertebrates and invertebrates. Entomologist Daniel P. Wojcik is working with many environmental and conservation groups to keep fire ants from harming endangered species like Stock Island tree snails, gopher tortoises, Florida grasshopper sparrows, saltmarsh rabbits, and sea turtles.

|

|

"Only 300 female green sea turtles are nesting in the world, and most of them are in Florida. Fire ants attack the immature turtles, either killing or blinding them," he says. "Sometimes young turtles wander across a fire ant mound. Fire ants usually sting them as a defensive response. But they will also attack and feed on anything that doesn't move, including animals."

An emerging anomaly and problem with fire ants is polygyne, or multiple-queen, colonies. "These 'super colonies' are more problematic than monogyne, or single-queen, colonies because, collectively, they lay more eggs and are harder to control," says chemist Robert K. Vander Meer.

Many people think if you kill the queen, you kill the colony. But this isn't true if there are workers left, says Vander Meer. Workerless colonies will adopt new queens, which provides one explanation as to why ants have reinfested treated areas and may be related to how polygyne colonies form.

|

|

The queen controls adoption and other colony functions through pheromones. Vander Meer says the ultimate goal is to find these pheromones and use them to help decrease fire ant populations. Scientists in this research unit have developed and applied for patents on new repellants, attractants, and multiple-species ant baits, all of which could soon help ease the fire ant burden.—By Tara Weaver-Missick, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Arthropod Pests of Animals and Humans, an ARS National Program described on the World Wide Web at http://www.nps.ars.usda.gov/programs/appvs.htm.

The scientists mentioned in this article are in the USDA-ARS Imported Fire Ants and Household Insects Research Unit, 1600 SW 23rd Dr., Gainesville, FL 32608; phone (352) 374-5903, fax (352) 374-5818, e-mail rbrenner@gainesville.usda.ufl.edu.

Native Habitat May Hold the Key

Most people think of Buenos Aires as a vacation spot. But for ARS entomologist Juan Briano and biologist Luis Calcaterra, it's a place for serious research. ARS' South American Biological Control Laboratory in Argentina helps the agency's North American scientists study exotic pests from Latin America.

Some pests are quarantined from import to the United States, so ARS' international locations are vital to studying them in their original environments.

Researchers in Buenos Aires helped ARS scientists from Gainesville, Florida, identify biological controls for fire ants, and now they are helping to ensure that these useful ant-busters don't harm native U.S. species.

One biocontrol agent they studied was Thelohania solenopsae, a pathogen that weakens and eventually kills fire ant colonies. "To study field host specificity of Thelohania, we traveled to rural areas of the Buenos Aires Province," explains Briano. "We put 300 bait traps in 30 field sites. We captured many ant species and took them back to the lab. There we froze them, ground them in water, and checked for the presence of Thelohania. We found it only in fire ants."

Briano and Calcaterra traveled to the San Eladio area 80 kilometers west of Buenos Aires to check for a parasitic ant, Solenopsis daguerrei. That area is heavily infested with fire ants, and S. daguerrei has infested many of the colonies.

"We checked a total of 4,131 fire ant nests and 185 nests of other ant species and found the parasite only in fire ant nests," says Calcaterra.—By Jill Lee, formerly with ARS.

Juan Briano is with the USDA-ARS South American Biological Control Laboratory, c/o Agriculture Counselor, U.S. Embassy, Buenos Aires, Unit 4325, APO AA 34034-0001.

"Ouch! The Fire Ant Saga Continues" was published in the September 1999 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.