Fighting a Fungal Siege on Cacao Farms

|

|

Americans love chocolate. Unfortunately, so do three pathogenic fungi that attack cacao trees, Theobroma cacao. These trees produce the pods that contain the beans used for making chocolate. The fungal infections lead to diseases known as black pod rot, frosty pod rot, and witches'-broom.

Black pod rot is caused by Phytophthora species. They are cousins to the fungi that cause pepper blight and late blight of potato. Probably about five or more different species of soilborne Phytophthora cause the pod rot disease that also attacks seedlings and causes cankers on stems, trunks, and crowns that are actually the base of cacao trees.

Frosty pod rot, caused by Moniliophthora roreri, produces masses of spores that appear as a white or tan powder on the pod's surface. The disease distorts the pods; they become asymmetric or develop a mosaiclike pattern of green, yellow, and cream. It rots the pod's interior and destroys the beans.

Witches'-broom is caused by Crinipellis perniciosa. This fungus causes the tree to send up a spray of crazy shoots from its flower clusters and branch tips and also infects the pods, making them unusable. Witches'-broom severely reduces the ability of trees to produce pods filled with beans.

"All three fungi have caused severe yield losses to the 3-million-ton annual cacao bean crop," says Eric M. Rosenquist. He is international program coordinator for the Agricultural Research Service's National Program Staff. "The fungi have inflicted economic hardship on the 5 to 6 million small farmers in South America, Africa, and Asia who produce and depend on the annual cash crop."

Where Cacao's a Top Crop

Brazil exports about $100 million in cacao beans to the United States annually and has traditionally been the top South American cacao exporter.

But witches'-broom—and other problems—have made Brazil slip to eighth place in the past 5 years.

"In 1992, Bahia, Brazil, was the world's second biggest producer of cacao," says John B. Lunde, director of international environmental programs for M&M Mars, Inc., of Hackettstown, New Jersey, one of the world's largest chocolate manufacturers.

"Harvest and export to the United States of Brazilian beans from Bahia have plummeted from 430,000 tons in 1985-86 to about 130,000 tons today. The major culprit is witches'-broom disease," says Lunde.

M&M Mars and other importers of cacao beans are concerned that West African countries, the current major exporters of cocoa, cannot handle alone the world's growing appetite for chocolate. The Ivory Coast supplies about 50 percent of the cacao beans for the world. Such reliance could endanger the U.S. supply of beans in cases of drought—which is not unusual—political unrest, or high rates of infection with Phytophthora or other disease-causing pathogens.

To find a solution to cacao's fungal problems, Rosenquist went to ARS plant pathologist Robert D. Lumsden at the ARS Biocontrol of Plant Diseases Laboratory (BPDL) in Beltsville, Maryland.

Rosenquist says the lab is "uniquely suited to solving these problems. Based on methods developed by ARS, biocontrol products are now being marketed to control several pathogens of greenhouse, fruit, and vegetable crops." "Not all these fungal pathogens are problems in all cacao-growing regions," says Lumsden. "Current strategies available to control the diseases include cultural practices such as pruning diseased trees and cleaning up infected pods and branches; spraying with copper-based fungicides; and breeding trees for resistance."

"Chemical controls for the fungi don't work very well and are expensive," says M&M Mars microbiologist Prakash K. Hebbar, who is working with Lumsden at Beltsville. "But," Hebbar notes, "cultivars tolerant of the fungal diseases are largely unidentified or have not been propagated in sufficient quantities."

"The ARS program represents a major step forward in cacao disease research and brings important cutting-edge science, skills, and needed technical leadership to a serious global problem that threatens the long-term health of the chocolate industry," says Lunde.

"Eric Rosenquist's program is making an important and essential difference. The program is also providing some needed hope to many small cacao farmers facing financial ruin and to environmentalists concerned about the loss of cacao agroforests."

Hebbar and Lumsden are part of a cooperative research project that includes various national and international research institutes. Their goal is to identify biological control strategies to be used in integrated pest management (IPM) systems to fight these diseases.

Research strategies include combining environmentally compatible biological control techniques with resistant cacao lines and using cultural practices that encourage sustainable cacao cultivation in the natural forest ecosystem.

It Takes a Consortium

The international effort is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, coordinated by Rosenquist; the American Cocoa Research Institute (ACRI) in McLean, Virginia; and M&M Mars, Inc.

Cooperators include ACRI; Comissião Executiva do Plano da Lavoura Cacaueria (CEPLAC) in Itabuna, Brazil; CABI-Bioscience in Ascot, United Kingdom; Servico Nacional de Sanidad Agraria of Lima, Peru; U.S. Agency for International Development in Washington, D.C.; the Organization of American States in Washington, D.C.; the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama City, Panama; Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE) in Turrialba, Costa Rica; Pennsylvania State University; and the University of Maryland's Wye Institute, Eastern Shore.

One of a few successes reported thus far came from a Brazilian scientist, Cleber N. Bastos, of CEPLAC, and British scientist Harry C. Evans, of CABI-Bioscience. They discovered a beneficial fungus, Cladobotryum amazonense, with potential for use in biocontrol of witches'-broom.

Bastos also discovered a fungus—which he initially identified as Trichoderma viride—that inhibits witches'-broom. He showed how this species was effective in suppressing the witches'-broom pathogen under laboratory conditions by actively parasitizing it.

Hebbar asked ARS mycologist and Trichoderma expert Gary J. Samuels at the Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory at Beltsville for help in identifying the beneficial fungus.

Samuels' job is to describe and catalog new species of fungi for USDA's U.S. National Fungus Collection, the world's largest herbarium of fungal specimens—about 1 million—at Beltsville. His work lays the foundation for other scientists who, like Lumsden, develop biological agents to combat pathogenic fungi that destroy crops.

Also Out of the Amazon

Samuels says many biocontrol fungi belong to the genus Trichoderma. Using both morphological and molecular characteristics, he discovered that the fungus which parasitizes the witches'-broom fungus had been misnamed. Differing from T. viride in its appearance and DNA characteristics, it was renamed T. stromaticum.

"It's a new species of Trichoderma from the Amazon Basin of Brazil," says Samuels. "Trichoderma is one of the most often used biofungicides. In experiments, it has controlled other diseases caused by Phytophthora species, the organism responsible for crown rot of apple trees. It also controls various species of Pythium and Rhizoctonia—soilborne fungi that cause damping-off diseases in seedlings of agricultural and nursery crops."

"Commercial formulations of other Trichoderma species are the fungi most often used as biofungicides," says Lumsden, "including SoilGard, a form of Trichoderma (syn. Gliocladium) virens developed by the BPDL."

Initial small-scale field and lab trials conducted in Brazil in collaboration with J.L. Bezerra and J.B. Costa at the CEPLAC research center showed that T. stromaticum could reduce formation of fruiting bodies, or basidiocarps, of the witches'-broom fungus by 99 percent when brooms were in contact with the soil, and by 56 percent in brooms remaining on trees. It reduced pod infection by 31 percent.

To confirm these results, several labs in cacao-growing countries are scaling up production of strains of biocontrol fungi, including T. stromaticum, in collaboration with BPDL scientists. Large-scale field trials are being performed in Bahia, Brazil, at CEPLAC and at M&M Mars' Almirante Farm, Center for Cacao Studies; at the CABI-USDA Project in Huallaga Valley, Peru; and at CATIE in Costa Rica.

Putting the Heat on Frosty Pod

"After frosty pod rot arrived in Peru in 1991," says Hebbar, "cacao production fell from 1,236 tons in 1992 to 427 tons in 1993. Pod yields of 520 pounds of beans per acre were well below the national average of 781 pounds per acre. Losses of up to 100 percent and the lack of economical disease control led to neglect and abandonment of cacao fields. This made cacao production even less profitable."

In January 1997, under the direction of CABI-Bioscience's Ulrike Krauss, USDA and CABI-Bioscience started the biocontrol of cacao disease project in Peru. For the first year of trials, the scientists used three abandoned fields that were highly diseased. Flowers and pods of 20 trees per treatment were sprayed monthly with a mixture of five strains of Trichoderma species.

"Results of these tests are very encouraging," says Hebbar. "Frosty pod rot, the main disease in Peru, was reduced significantly—by about 49 percent, under a wide range of growing conditions.

Biocontrol improved the number of healthy pods by about 62 percent in all fields, though yields increased only in the shaded plots where disease was controlled early. Yields were raised considerably more with a mixture of the five biocontrol strains than with a single one.

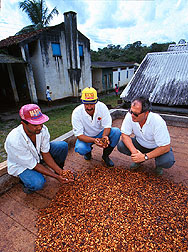

Producers on small farms like Fazenda Santa Maria, near Uruçuca, are searching for alternative crops that will enable them to survive if cacao-destroying fungi cannot be curbed. (K8622-1) |

Still a Lot To Learn

Hebbar says that "biocontrol agents that are adapted to a variety of conditions are being studied and should be tested. These organisms are from the cacao environment and may perform best if combined into mixed sprays to cover the entire range of conditions."

Initial results showed that to be most effective, biocontrol sprays must be applied at the peak of flowering.

Cacao cultivation can be managed best under the shade of the tropical rainforest. "Growing cacao trees under the rainforest shade canopy, or cabruca, protects the trees and allows biocontrol sprays to last longer and remain more effective," says Hebbar.

"The biocontrol fungal sprays were produced in one of two ways," he adds, "either as a preparation in sterilized liquid cultures or as a solid substrate preparation—both composed of desiccation-resistant spores of the fungi."

ARS scientists are investigating how the new Trichoderma species works to control witches'-broom. Learning the mechanism of action may provide clues for enhancing biocontrol activity. They are also trying to improve the economical mass-production of the beneficial fungus.

"This would make it easier and more cost effective for small farmers to use," says Hebbar. At the M&M Mars, Inc., Almirante Farm, microbiologist Smilja Lambert oversees seven experiments involving monthly spraying of new Trichoderma strains. Almost 12,000 cacao trees are included in these trials.

Results from harvesting pods showed that fewer pods per tree were infected by witches'-broom when trees were treated with the Trichoderma strains and pruned—compared with untreated and unpruned controls.

"We found that combinations of biocontrol agents were more effective than a single strain," says Hebbar. "Time of application and shade conditions are crucial for biocontrols to be effective. We will continue to evaluate spore types of biocontrol agents for their efficacy."

Boosting Biologicals

With the exception of facilities at CEPLAC and the M&M Mars Almirante Farm in Brazil, facilities to mass-produce biocontrol agents are currently lacking in Latin America. Scientists in Peru are scaling up their facilities to mass-produce the agents.

To better evaluate the disease-control potential of biocontrol agents currently available and being used in small field trials, Hebbar says, "it will help to have scaling-up fermentation and formulation facilities with carefully monitored quality-control protocols."

Current facilities must be upgraded to mass-produce biocontrol agents. Then, these agents must be tested as soon as possible at field sites with the agricultural extension network and other agencies, says Hebbar.

Cooperative research agreements are currently in place to transfer technology from ARS and CABI-Bioscience to scientists in Peru, Panama, and Costa Rica to mass-produce biocontrol agents, test them under field conditions, and improve methods of applying them.

"The emphasis will be on developing integrated pest management strategies, as well as on mass-producing the agents themselves," says Lumsden.

The IPM technology to control cacao disease epidemics will be helped by a cooperative project funded jointly by ARS, ACRI, and M&M Mars to predict disease outbreaks and manage and protect natural resources, soil and water ecology, and cacao genomics.

"Biocontrol is not a magic bullet that will suppress all three major fungal diseases," says Hebbar. "Applying biocontrol sprays along with pruning, proper plant nutrition, and use of disease-tolerant cultivars should improve yields by lessening the incidence of disease."—By Hank Becker, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff..

This research is part of Plant Diseases, an ARS National Program (#303) described on the World Wide Web at http://www.nps.ars.usda.gov/programs/cppvs.htm.

Robert D. Lumsden and Prakash K. Hebbar are at the USDA-ARS Biocontrol of Plant Diseases Laboratory, Bldg. 011A, 10300 Baltimore Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705-2350; phone (301) 504-5872/7985, fax (301) 504-5968.

C h o c o l a t e

Delicious & Nutritious!

Not only does chocolate taste good, it may be a good source of phytochemicals and essential micronutrients, too.

Recent Agricultural Research Service studies in cooperation with the University of California, Davis, and M&M Mars, Inc., show chocolate contains a variety of compounds that may contribute to cardiovascular health. In addition to carbohydrates, fats, and protein, it contains several micronutrients, including the minerals iron, potassium, and zinc, and is especially rich in magnesium, copper, and manganese. Also present are B vitamins—riboflavin and niacin.

Though relatively high in vegetable fat (50 to 55 percent), cocoa butter has been shown to have no effect on blood cholesterol levels in humans. That's because of its unique fatty acid composition, which is mainly stearic and oleic acids. Cocoa is also packed with antioxidants that may help cut the risk of developing cancer and heart disease.

Because of the emerging body of evidence that links phytonutrients and long-term health, ARS has put together a world-class team of researchers led by nutritionist Beverly A. Clevidence, who heads the Phytonutrients Laboratory in Beltsville, Maryland. ARS and M&M Mars, Inc., are collaborating to better understand the phytonutrient potential of chocolate and cocoa.

"Fighting a Fungal Siege on Cacao Farms" was published in the November 1999 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.