No Muss, No Fuss Spray Rig for Greenhouses

Around the ARS Crop Science Research Laboratory at Mississippi State, Mississippi, maintenance mechanic Stan Malone is regarded as an engineering wizard.

Last summer, Malone put his exceptional talents to work when Quinnia L. Yates, a biological lab technician, proposed the idea of automating an insecticide spray system for greenhouse-grown plants. After surveying Yates’ greenhouse, Malone envisioned an overhead pesticide-misting rig that might best fill that bill.

But none of the commercial greenhouse suppliers they later contacted sold any such rig matching his conception. “We tried everywhere,” Malone says, “but there was nothing out there we could find.”

His next move was to team up with Dennis Rowe, who heads up the lab’s Forage Research Unit.

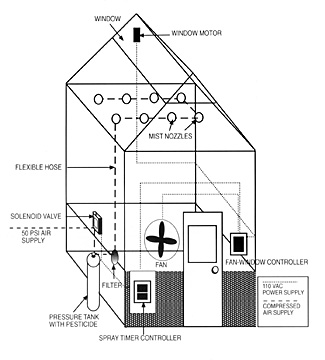

With the unit’s help, Malone then designed a system of his own—drawing on such off-the-shelf items as a toggle switch, timer clock, pressurized pesticide tank, chemical hoses, flora nozzles, and other components chosen from various commercial equipment suppliers.

With the new system, “there’s no human involvement except for mixing of pesticide according to the manufacturer’s label,” Malone says. “You simply fill your tank with whatever insecticide you need to control the insects, set the timer clock, and turn on the switch and leave.”

|

|

This activates electrical relays that temporarily close the greenhouse’s exhaust fans, motorized windows, and vents. A special valve attachment then releases compressed air into a 5-gallon tank, forcing pesticide into overhead hoses and brass irrigation nozzles. These mist the chemical over the plants, providing full coverage in 2-½ minutes for a 30- by 40-foot room.

The system then flushes its hoses clean with blasts of air and, after the pesticide settles, restarts the green-house's environmental controls.

Before the automatic system’s installation, it took Yates about 45 minutes to manually spray insecticide to curb populations of whiteflies, mealy bugs, and other destructive insects. Left unchecked, their feeding damage can jeopardize the uniformity of plants grown for research. But 1994 EPA worker protection standards—while effective—made routine spraying arduous, costly, and unpleasant.

The standards dictate that greenhouse workers wear a respirator, protective suit, gloves, goggles, and boots when spraying. But in a hot, humid greenhouse where temperatures can reach 110oF, a suited worker can easily become faint or dizzy.

Because of this, “we sometimes would neglect spraying until we got a buildup of insects,” Yates says. “But with the new spray rig, it’s not necessary to risk a buildup.” It also eliminates the need for the costly disposable suits.

The system can be set to spray at night or on the weekends. Also, “users can modify it to fit their applications,” says Malone. He has installed the new rig in 15 of the ARS lab’s 30 greenhouse rooms.

The costs for materials start at $700 for a 30- by 40-foot room. Computer-controlled foggers and other commercial devices that apply pesticide in greenhouses range in cost from $2,000 to $5,000. “The greatest gain I see,” says Rowe, “is knowing workers are not exposed to spray.”

Rowe, Malone, and Yates intend to submit detailed plans for the new system to a trade journal. — By Jan Suszkiw, ARS.

Stan Malone is at the USDA-ARS Crop Science Research Laboratory, P.O. Box 5367, Mississippi State, MS 39762; phone (662) 320-7447. Dennis Rowe is in the Waste Management and Forage Research Unit, phone (662) 320-7421.

"No Muss, No Fuss Spray Rig for Greenhouses" was published in the July 1996 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.