To Zap Medflies—Red Dye, Updated Traps

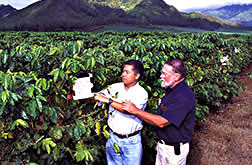

Entomologist Nicanor Liquido (left) and Roy Cunningham test C&C traps and a dye-based insecticide in Hawaiian coffee fields where medflies thrive. (K7016-20) |

Newly improved traps and an environmentally friendly, sun-activated insecticide may help spell doom for the Mediterranean fruit fly.

Versatile and voracious, the medfly ranks as one of the world's worst agricultural pests.

Medfly's maggot offspring can live snugly inside more than 300 different kinds of fruits and vegetables. They survive by eating their tasty housing.

To thwart the trouble some insect, ARS scientists in Hilo, Hawaii, and industry colleagues in California and Maryland are refining two new and improved medfly traps.

And the Hawaii scientists are collaborating with ARS researchers at Weslaco, Texas, to investigate phloxine B. better known as the FDA-approved red dye number 28. The dye, says entomologist Roy T, Cunningham at Hilo, might prove a safe, effective alternative to today's malathion insecticide, Cunningham directs the ARS Tropical Fruit and Vegetable Research Laboratory headquartered at Hilo.

A female medfly pumps eggs through her ovipositor into the soft outer layers of a ripe coffee berry. (K7022-6) |

The updated traps and colorful dye, he says, could also help shield Hawaii's orchards and fields of exotic tropical crops from resident medflies. For sunbelt states like California and Florida, where medflies would like to live. The inventions may forestall medfly invaders' gaining a foothold.

In mainland states vulnerable to medfly attack, traps suspended from tree limbs and bushes serve as sentries to ensnare roving medflies.

When a routine inspection of the traps reveals a captured medfly, agricultural agencies can move quickly to snuff out the remaining intruders, before the population builds.

These traplines might someday feature the C&C trap, a device invented by Cunningham and entrepreneur John M. Cook of Farma Tech International in Fresno, California.

The invention consists of a metal hook or hanger and a plastic holder—about the size of a chalkboard eraser—that has three panels hanging down from it. The center panel is a thin, 6-inch-by-6-inch sheet of rigid plastic, impregnated with a lure that it releases slowly. About an inch away, paperboard panels coated with a sticky compound hang down on either side of the center panel. All the panels slide neatly into the holder, making them easy to remove, inspect, and replace.

The chemical that wafts from the center panel lures male medflies to the trap. The sticky panels nab the curious flies on their way to or from the source of the attractive scent. Using sticky panels to catch medflies, says Cunningham, isn't new.

In fact, ARS researchers helped develop an earlier type of bright-yellow sticky trap for use in California.

Those panels, coated with a small amount of lure mixed in a sticky compound, are posted by the hundreds when medflies—hitchhikers in smuggled produce, for instance—make an unwanted appearance. The traps, however, usually last only 2 weeks before they run out of lure. The new trap, says Cunningham, emits lure for 2 months or more, so it should cost less to maintain.

In tests in California and Guatemala, the C&C trap did a better job of attracting and capturing medflies than two other types of traps currently used to detect them.

Another new trap sports a flashy yellow that attracts medflies. Known as the Merrill trap, this juglike invention is about 9 inches tall and is made of lightweight, high-tech plastic. The upper two-thirds of the trap is clear; the lower third is bright yellow.

Designed by Gary Merrill and Ray Harrie of Bio-Con Biological Control Systems in Mentone, California, the trap is a larger—and yet, less cumbersome—version of the all-glass McPhail trap.

Entomologist Nicanor Liquido and technician John Ross apply precise combinations of insecticidal dye-and-bait mixtures to cotton wicks, to see which concentrations medflies prefer. (K7020-19) |

States that run McPhail traplines would likely welcome a newer version that won't break as readily and should be simpler to maintain.

Both the McPhail and the Merrill traps have an inner reservoir that holds a mixture of water, borax, and a protein-rich bail made from corn or other sources. Though medflies can enter the jug easily, few of the insects figure out how to escape. Exhausted by their futile search for the enticing bait, the flies eventually fall into the elixir and drown.

The Merrill trap can hold three times as much liquid as the McPhail trap. "In hot weather," says Hilo entomologist Nicanor J. Liquido, "heat may completely evaporate the fluid in the McPhail. When that happens, the trap can't attract any more flies. But a Merrill trap should last about three times longer."

In tests on two islands in Hawaii, Liquido found that Merrill traps, in general, caught as many medflies as McPhails. He did the work with ARS colleagues Paul G. Barr, Grant T. McQuate, John R. Ross, Charmaine D. Sylva, and Judy M. Yoshimoto.

In the Pink

When incoming medflies are captured in mainland traps, aerial spraying of malathion insecticide may follow. But malathion could eventually be supplanted by an insecticide made from the same FDA-approved dye that pinkens some of America's most popular medications. PhotoDye International of Linthicum, Maryland, has patented the use of several FDA-approved dyes as insecticides.

The Hilo scientists' laboratory and outdoor tests with one of these compounds—D&C red number 28—showed that eating the dye and catching some rays is a lethal combination for medflies.

"On a sunny day, a medfly that breakfasts on the dye may be dead by lunchtime," says Liquido.

His tests were the first to prove the dye's ability to trap medflies. The findings agree with earlier work done with other insects by James R. Heitz, PhotoDye president and a biochemistry professor at Mississippi Stale University, along with ARS scientists in the Crop Quality and Fruit Insects Research Unit at Weslaco, Texas.

Medflies often share regurgitated food. This helps spread the insecticidal dye-and-bait blend through the population. (K7026-19) |

Experiments in Weslaco target a medfly relative, the Mexican fruit fly. Entomologists Robert L. Mangan and Daniel S. Moreno conduct the tests on this insect enemy of mangoes, citrus, and about a dozen other crops.

The Weslaco scientists have also cooperated with Jennifer L. Sharp at the ARS Subtropical Horticultural Research Laboratory in Miami, to show the dye's toxicity to the Caribbean fruit fly, a pest of guavas and citrus in Florida.

The Hawaii and Texas teams seek two kinds of ingredients. One is a bait that would attract the insects to the fatal meal. The other is a stimulant to boost the insects' appetites.

The Hilo researchers use lab-reared flies as taste-testers for new formulations. They turn groups of 20 flies loose at a time to forage in a small, clear-plastic bowl.

A cover of fine-mesh cloth blocks the insects' escape. Inside, flies can feed on carefully placed drops of the latest combination of dye, bait, and appetite stimulant. If a fly likes the test recipe and eats heavily, the dye soon changes the color of its belly from light-brown to crimson.

Unlike pesticides that begin to work as soon as an insect touches them with a leg or other part of its body, the dye blend kills only those flies that eat it. An experimental use permit granted earlier this year by the EPA allows the ARS teams to carry out larger tests of the dye-based insecticide in Hawaii, California, and Texas.—By Marcia Wood, ARS.

Robert L. Mangan is in the USDA-ARS Crop Quality unit Fruit Insects Res. Unit, Subtropical Agricultural Res. Laboratory, Weslaco, TX; phone (956) 447-6316.

Roy T. Cunningham, Nicanor J. Liquido, and colleagues were at the USDA-ARS Tropical Fruit and Vegetable Research Laboratory, P.O. Box 4459, Hilo, HI

"To Zap Medflies—Red Dye, Updated Traps" was published in the January 1996 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.