Bolstering Bone Health Through Nutrition Research

Agricultural Research Service nutrition researchers are intent on discovering more about the role nutrition can play in boosting bone health. In one study, for example, physiologist Marta D. Van Loan collaborated with scientists from Purdue University and elsewhere in exploring young girls’ perceptions of lactose intolerance. The 291 volunteers, ages 10 to 13, were participants in a larger study called “Adequate Calcium Today.”

The millions of Americans who are lactose intolerant may suffer digestive discomfort when they eat dairy products or foods made with those products. But dairy foods such as milk are an excellent source of calcium, an essential mineral that provides the structural support needed for strong bones.

Lactose-free products, from which milk sugar (lactose) has been removed, are designed to provide an alternative, so that lactose-intolerant kids and adults may enjoy calcium-rich dairy foods without incurring digestive problems.

In some instances, perception and biochemical reality were different. Results from the standard breath-hydrogen test for lactose intolerance showed that some girls who thought they were lactose intolerant actually weren’t. Other girls who actually were lactose intolerant didn’t know they had the condition until they tested positive during the study.

“We’re concerned,” says Van Loan, “that misperceptions about lactose intolerance can lead girls—in early adolescence—to cut back on milk. To do that during this phase of their critical bone-forming years could have lifetime consequences on the health of their bones.”

Van Loan is a coauthor of the 2007 article in Pediatrics that documents the study.

Weight-Bearing Exercise Really Does Work

In another study, published in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise in 2007, Van Loan and coresearchers took a closer look at how leisure-time physical activity affected the bone strength and bone geometry of 239 postmenopausal women. The decreased production of estrogen during postmenopausal years may increase risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and other conditions.

The researchers found that a minimum of 30 minutes a day—or, alternatively, 4 hours a week—of walking, jogging, weightlifting, or other weight-bearing leisure-time activity was needed to maintain two key indicators of bone health: cortical bone density (the thickness of bone’s hard outer layer) and functional geometry (such as the inner and outer diameter of the bone).

Soy Isoflavones: Still Controversial

While calcium and weight-bearing exercise are unarguable aids to bone health, soy’s role remains unclear. “Ever since conventional steroid hormone replacement therapy was shown to cause certain kinds of cancer and other side effects,” says Van Loan, “researchers have been looking for a safe and effective alternative for postmenopausal women.” Soy, as one potential candidate, has been the subject of more than two dozen studies conducted in the U.S. and abroad during the past decade. Some of those investigations have suggested that soy enhances bone health.

One such study, a 6-month investigation led by Iowa State University researcher D. Lee Alekel in 2000, showed that soy protein prevented bone loss in tests with 69 women volunteers who were entering menopause. That research paved the way for a 3-year investigation in which Alekel, Van Loan, and others studied whether isoflavones—estrogenlike compounds extracted from soy protein—protect postmenopausal women against bone loss.

Volunteers in the isoflavone study—the longest of its kind—took either a placebo tablet or a tablet containing one of two moderate amounts of the isoflavones—80 milligrams (mg) or 120 mg—every day.

Overall, the isoflavones “had no significant positive effect on preventing bone loss,” says Van Loan, “but there was a modest benefit of the 120-mg isoflavone treatment when evaluated in conjunction with lifestyle factors.

“The body’s response to isoflavones extracted from soy proteins may be different from its response to isoflavones in their natural matrix of soy protein or soy foods or in a soy-protein supplement,” she says. “It’s also possible that some soy-protein compound other than the extracted isoflavones was responsible for the bone-protecting effects seen in some studies. Or the doses of the isoflavones in our study may not have been high enough to produce a bone-sparing effect.”

An article published by the team earlier this year (2010) in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition has further details.

|

|

The Calcium Needs of Adults

Other ARS researchers are taking a new look at the calcium requirements for adults.

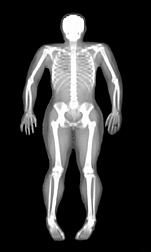

The body’s skeleton clearly needs adequate dietary calcium to reach its full potential in terms of bone mass. But other factors also affect bone mass, such as smoking and vitamin D intake.

Currently, calcium intake recommendations vary markedly between countries. For example, for adults over age 50, the recommended calcium intake is 1,200 mg daily in the United States—but in the United Kingdom, it is 700 mg daily.

A study led by former ARS biologist Curtiss Hunt and statistician LuAnn Johnson suggests that the current recommended amount of dietary calcium for American adults may be greater than actually needed.

Hunt and Johnson analyzed data collected from 155 male and female volunteers, ages 19 to 75, who participated in at least 1 in a series of 19 controlled feeding studies conducted at the Grand Forks (North Dakota) Human Nutrition Research Center.

The modeling of the data suggests that the average amount of dietary calcium needed to maintain a neutral calcium balance is about 741 mg per day. “Calcium balance” is the condition wherein the amount of calcium consumed equals the amount of calcium lost through elimination.

“The same model suggests that a calcium intake of 1,035 mg per day would cover the needs of 95 percent of the American adult population,” says Johnson.

The volunteers’ bodies tried to maintain a relatively stable amount of calcium even though their daily intakes of calcium varied widely—415 mg on the low end to 1,740 mg on the high end. When fed the lower amounts, for example, the body was more efficient in keeping calcium. When fed the higher amounts, the extra calcium was simply eliminated.

The study was published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 2007.—By Marcia Woodand Rosalie Marion Bliss, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Human Nutrition, an ARS national program (#107) described at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

Marta D. Van Loan is with the USDA-ARS Western Human Nutrition Research Center, University of California, 450 W. Health Sciences Dr., Davis, CA 95616; (530) 752-5268.

LuAnn Johnson is with the USDA-ARS Grand Forks Human Nutrition Research Center, 2420 2nd Ave. N., Grand Forks, ND 58203; (701) 795-8408.

"Bolstering Bone Health Through Nutrition Research" was published in the July 2010 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.